Meditations on AI and the Future of Business

[Apologies in advance for the rambling. This one is a bit longer than the usual]

I.

We're in for a wild ride.

That's been my general emotional state since December, but really that's been my general emotional state since the original GPT3 release back in 2020.

I've spoken in the past about information arbitrage — gaps of knowledge where some small group of people know something that the general populace doesn't. Like all arbitrage opportunities, you can extract value by simply sharing information.

That was, to a first approximation, Jasper's business model.1 Jasper didn't build the core tech behind GPT3. They didn't build any core tech at all! The main value they were bringing was essentially market making — they were connecting people who want access to something like GPT with OpenAI's API. They were a sales team bolted onto Ilya Sutskever's research lab. Now that everyone knows about GPT and OpenAI is a household name, Jasper's business model has basically run its course.

That doesn't mean the information arbitrage is gone. Sure, that particular opportunity no longer exists, you can't make a business on the back of telling people what LLMs are anymore. But if anything, the gap between "what the tech can do" and "what people think the tech can do" is much much wider than it was before. People on the inside are preparing for a world where "work" as we know it no longer exists. I have friends who are L6 and L7 engineers at Google (read: very very senior) who are talking to me about finding new areas of work because the AI will come for their job in 1-2 years.

A sea change is coming, and it's hard to stare at the sheer size of the tsunami without trying to rationalize it in some way.

Luckily, one of the benefits of being a one-time liberal arts student is the awareness that there is nothing new under the sun. This isn't the first time we've been faced with a truly revolutionary technology, as a species; there are lessons and patterns in the past that might help us prepare for what's to come.

II.

I've been thinking a lot about the history of the video game design industry, and I actually wrote a bit about gaming as an analogy to the current moment back when I was reviewing O3 a few months ago. I wrote:

With O3, you can hire an automated PhD in anything you want for less money than dinner in Manhattan. And, of course, the price will drop. The question now is when, not if.

At a societal level, this is not a bad thing! The spread of these tools will lead to an explosion of automation and application as non-technical laymen find that they can build directly. As a parallel, I think a lot about the video game industry. In the early days, game development was limited to programmers who were capable of developing on bare metal. These guys were wizards, able to extract incredible performance from limited hardware. But there were maybe 100 guys like that in the entire world. The release of game engines like Unreal and Unity meant thousands of people could create games without having to learn assembly, and that in turn led to an indie explosion.

In the 80s, if you wanted to make games, you had to be a John Carmack level programmer. John Carmack wasn't the best person in the world to make games. He probably wasn't even in the top 100. But among the people who knew how to code on bare metal and could directly write assembly — that is, among those who had the requisite engineering talent — he was number one.

Fast forward twenty years. When Unreal and Unity (and game maker and flash and godot and…) came out, they lowered the barrier to entry to make games. Like, a lot. I got my start making games on Unreal back in sixth grade and I assure you I was not doing any assembly. When the barrier to entry to making games cratered, a bunch more people very predictably started making games. And what's interesting is that they weren't just making the same kinds of games that Carmack was making. They were making games that were unique — games that focused on art style, or music design, or gameplay. Games that felt like movies, or stories, or puzzles. Games that pushed the boundary of what games could be.

The result of a lower barrier to entry meant variety, as individuals with unique skills and perspectives filled every possible niche. By 2008, with the massive success of Braid, the indie game explosion was in full swing.

Lowering the barrier to entry also meant a fundamental rethinking of the kinds of business structures that were necessary to support a video game developer. Before off-the-shelf game engines, most folks who were releasing games were behemoth companies like Sega, Nintendo, Atari, EA. Sure, there were exceptions. Dwarf Fortress was two guys, so was Myst. But the vast majority of games required large support structures because these companies were busy building the games and the engines that the games ran on and the hardware those engines ran on.

Unreal, Unity, and their ilk created an environment where you didn't have to work at a 700 year old Japanese company to make games. You could be, like, one not-particularly-technical guy working out of his parents place. That in turn led to the rise of significantly smaller teams who could move a lot faster and were less beholden to the financial requirements of a triple-A studio2, as well as alternative funding sources like Kickstarter.

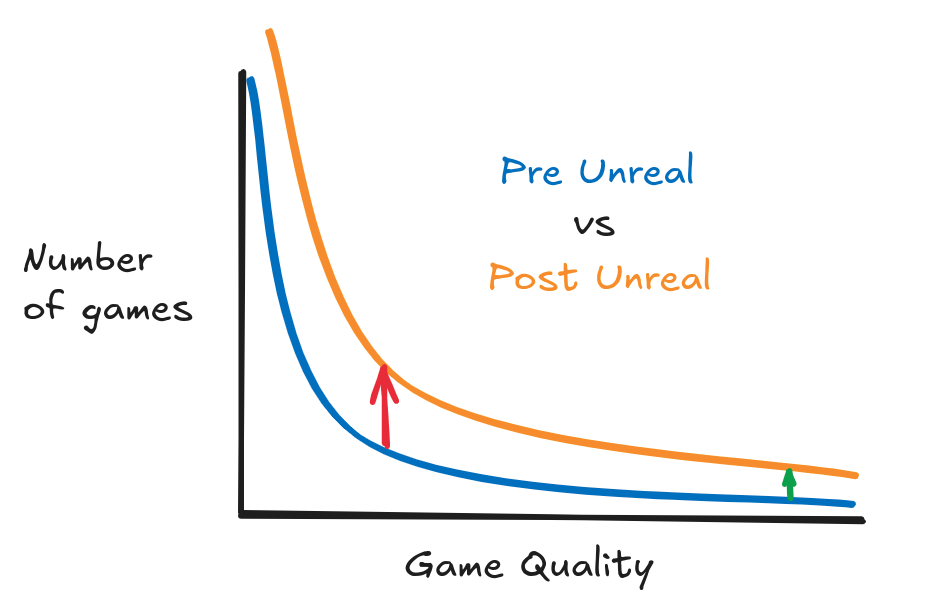

Games follow a power law distribution in terms of quality. Most games are crap, and a very small percent of them are good. The average person who plays video games only really cares about the small percent that is actually good.

Tools that lower the barrier to entry don't change the shape of this distribution. Rather, they raise the entire distribution up. The best games get, on average, even better, and there are more of them to go around; but there are also way more bad games, and most of the time the absolute increase in bad games is much larger than the increase in good games. Put bluntly, the average indie game is terrible. Sixth grade Amol was not producing greatness. In modern terminology, Unreal and Unity and even Flash enabled a lot of "slop", as random people without expertise started producing and releasing video games.

You could imagine an environment where the overwhelming increase in bad games saturates the market, resulting in the games industry dying. But that's not what happened, not even close. For the most part, everyone was and is able to ignore the slop thanks to market innovations.

As the quantity of games increased it became increasingly important to identify quality. Taste began to matter a lot more; the market demanded curators who could guarantee some level of consistency for the broader consumer audience. In the early days, quality came out of brand familiarity. Many gamers like Nintendo because Nintendo games are generally really high quality, and for a while Nintendo actually capitalized on this by stamping games they liked with an 'official seal of approval'.

As the games industry got bigger, the market grew capacity for individual niche reviewers — videogamedunkey makes a living off playing, reviewing, and recommending games to his audience, while publications like IGN exist entirely to review videogames.

And finally, at a certain size, the industry developed marketplaces to serve as a single point of entry for customers looking to buy while also providing decentralized community review services. This started with brick and mortar stores — think GameStop — but eventually moved online. Steam is now the marketplace for games. It has a catalog of some 85k games, each one reviewed and curated by the larger community. Steam has systematized and decentralized rating mechanics that allow good games to float to the top, rewarding people who make popular and well liked games while ensuring consumers do not have to wade through piles of trash to find something they might enjoy. And Steam acts as a central watering-hole of sorts — publishers and consumers alike benefit from having a one stop meeting ground to discover and buy games.

So to recap, a lower barrier to entry in the video game industry meant:

Massive increase in quantity and variety of output;

A shift in viable business structures;

An increase in the importance of taste and curation.

III.

These patterns aren't unique to gaming.

In the fashion industry, roughly the same thing played out. First you had high barriers to entry, and only the people who had the materials and expertise to make clothes made clothes. Then the barriers dropped to the ground in the industrial revolution. And now you have an environment where just about anyone can make clothes, a lot more people do make clothes to fill every niche, and taste (in the form of companies like LV or Gucci, who both curate and create) matters a lot more.

In entertainment, making movies and music used to require expensive equipment and entire production teams. Then you got a slate of improvements — cheaper cameras, better recording devices, DAWs, as well as decentralized distribution platforms like YouTube and Spotify. And of course that's led to more content, with greater variety, created by more people.

Hell, you can go all the way back to the printing press. Originally it was very hard to print books. The printing press was invented, which significantly lowered the barrier to entry. This resulted in much more variety (beforehand just about everything was religious texts!), an increase in authors, and so on.

Hopefully the parallels are obvious.

AI makes it easier for everyone to code. We should expect that this will dramatically increase the quantity and variety of software, enable new business and funding structures, and increase the importance of curation.

Except AI doesn't just make it easier for everyone to code. To a first approximation, AI makes it easier for everyone to do everything. And this gets weird really fast.

IV.

I used to play jazz saxophone. I wasn't particularly good. I could play a few standards and every now and then would do a solo that was exactly fine. But I had fun with it, a lot more than learning to play classical piano or whatever. Jazz was interesting because there were two distinct parts to it. There was some amount of baseline technical excellence. You had to know how to read music, how to get the right notes out of your instrument, how to think in terms of chords and progressions. And there was some amount of artistry. When you were on stage, where was the music going to take you? How good was your instinct? What would you do with a particular riff, or a back and forth? How would you build on the musical themes, put your own spin on it? And there were musicians who were fantastic at the former, folks like Count Basie or Buddy Rich, and others who mainly were great at the latter — Mingus, Coltrane, etc.

I think basically every job has a split like this, some distinction between technique and taste.

When you hire someone, you're hiring them in part for their understanding of the technique — does a graphic designer know how to use Photoshop? does a banker or trader know how to use the Bloomberg terminal? does a programmer know git? And you're hiring them in part for their taste — do they create beautiful art / find good trades / build useful and maintainable products? That sort of thing.

All things being equal, it would be great to hire someone with a lot of taste and a great grasp of technique, but those people are expensive, so you compromise somewhere. Depending on the job, you might care about the technique more than the taste or vice versa. If I'm producing a major exhibit for a snazzy gallery in Chelsea, I'm going to really care about the taste of the people who are going to be part of the exhibit. But if I'm, like, looking for some graphic for my blog post, I maybe don't need to hire Picasso? I can just hire someone who knows Photoshop reasonably well.3

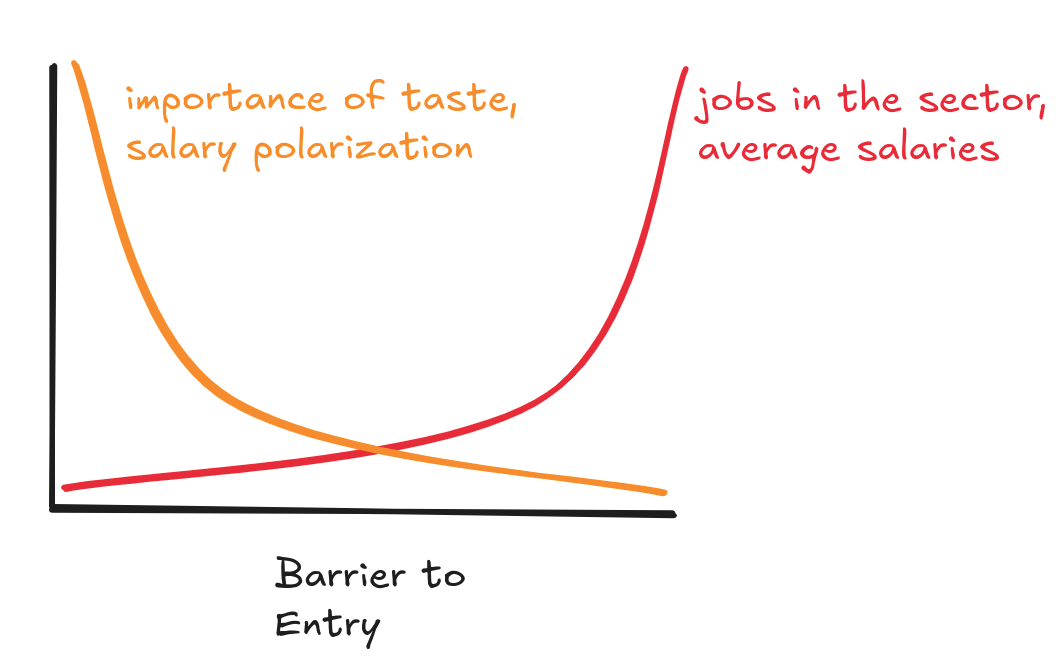

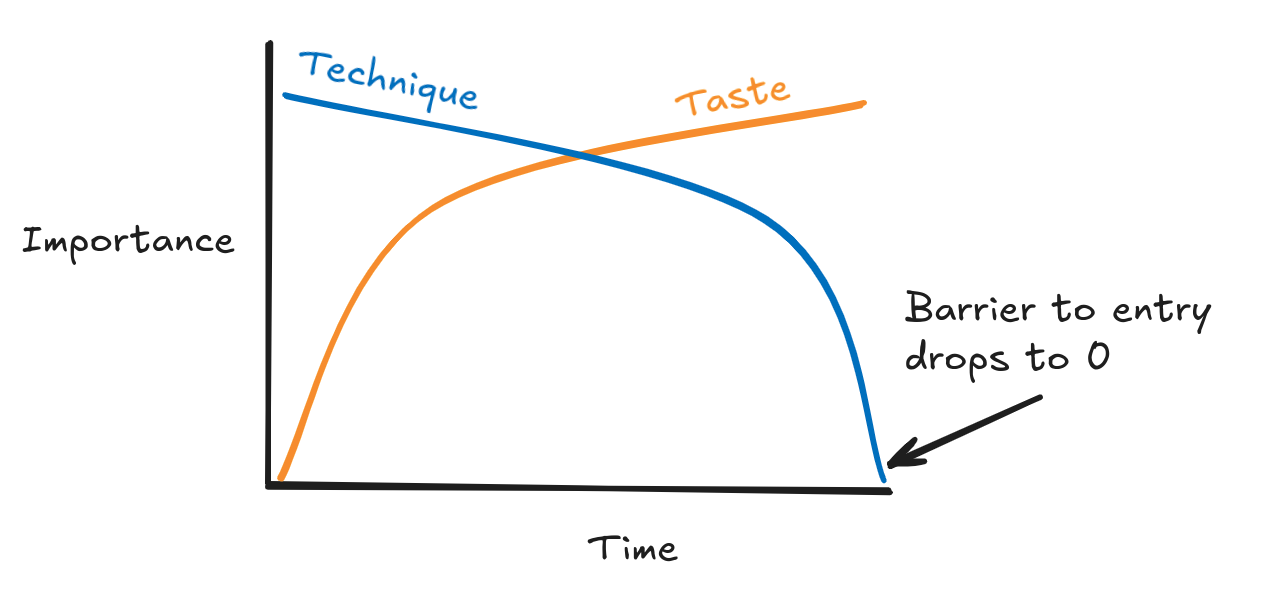

I think there's an arc that can be drawn over a long enough timespan that charts the relative importance of technique and taste. It looks something like this:

In the early days of a given career path, just knowing technique is enough to be valuable. The job is new! There probably aren't that many people in the world who can even do the bare minimum! No one cares about taste! This is the world that John Carmack was in when he was making games.

Over time, though, the value of technique goes down. Technology improves, making it easier for newcomers to learn the ropes, or maybe education systems adapt to changing requirements and more students learn the basics in school. Whatever the cause, as a career path matures the demand for taste becomes greater inversely proportional to the ease of access.4

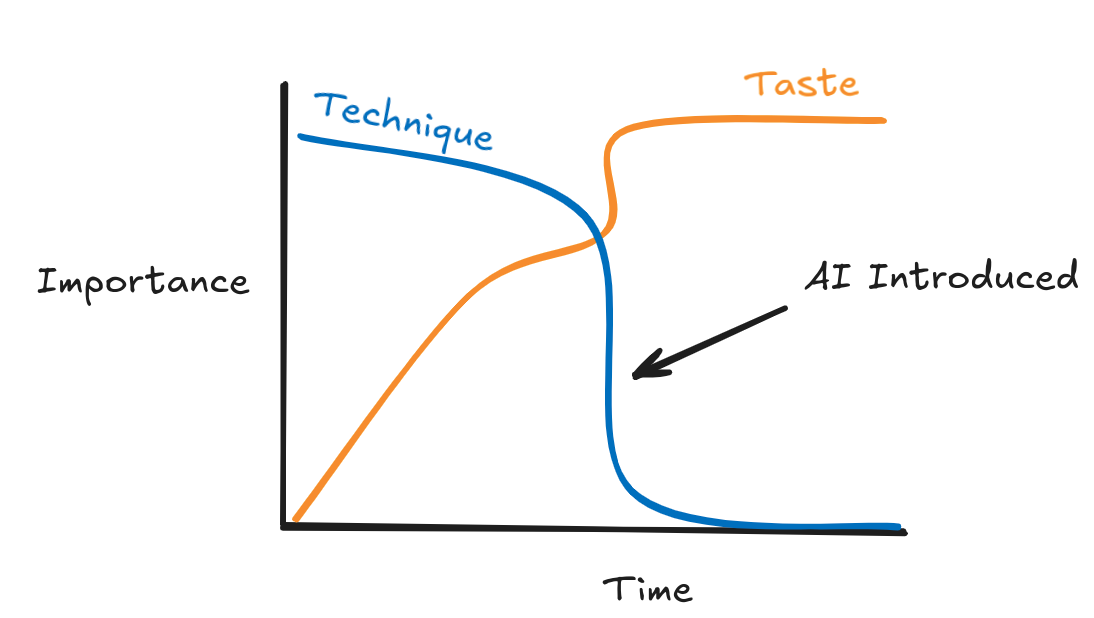

AI does this weird thing, where instead of getting this nice smooth curve you actually have something like this:

In a very short period of time, the importance of technique just drops to the floor.

So far I've written a lot about who benefits from AI. Assuming AI doesn't kill us all (big assumption!), the lower barriers to entry seem broadly good for consumers, for newcomers to a field, and plausibly for the field itself. But AI is really bad for people who stake some or maybe all of their career on 'knowing arcane shit that other people don't know'. This is basic supply and demand — as the need for technique drops, the value does too. With AI, this hits everyone in every field all at once.

We've seen some of the effects of AI in the art industry. The release of diffusion models has basically blown up the freelance market for digital assets. A lot of folks who previously were able to get commissions just off the back of being able to create assets at all are now struggling for contracts. Meanwhile, the people who previously would have sprung for custom artwork are finding ways to do it themselves.

Programming seems like it's next up on the chopping block. And, look, if you're a programmer, I don't care how beautiful your code is or how good you are at system design, a chunk of your salary comes from the fact that you know how to program and most people don't. You and only a select few others know the strange runes that you can punch into a computer to get it to do magical things, and you get paid for that.

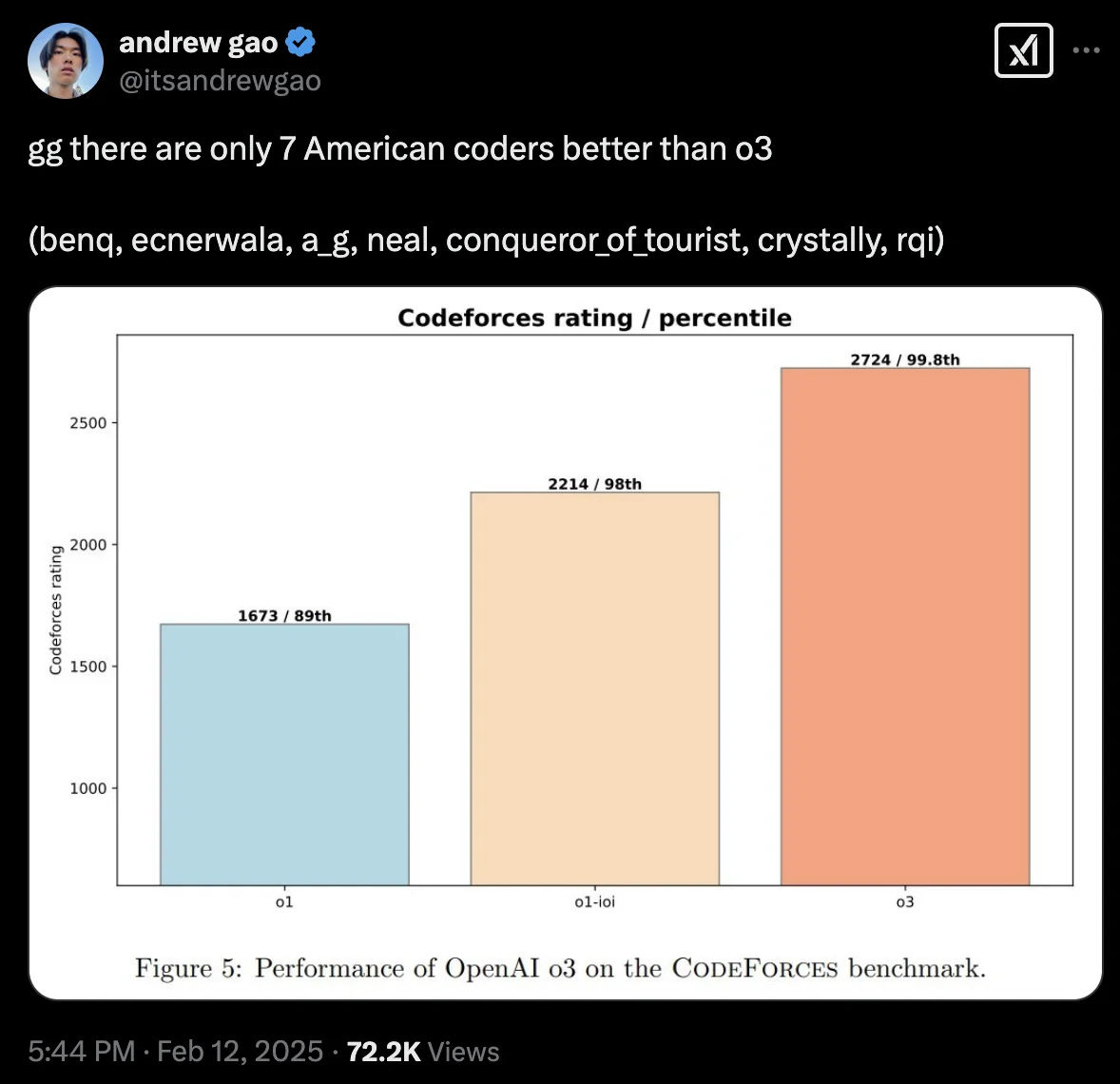

OpenAI claims that o3 is one of the best competitive programmers in the world. There are, supposedly, only 7 other people in the entire country that are better at programming than o3. So the magic runes are available to everyone now. What do you think that will do to your salary?

V.

Assume that there are five senior engineers at a company. Each can produce 4k lines of code a month, or 20k total. And let's say AI gets good enough that it can empower a single senior engineer to be 5x more productive.

There are two possible extremes here.

On one hand, the company could decide that it does not need the extra code. The primary company bottleneck is not feature dev or maintenance, so it just doesn't need the extra coding power. In this world, the company holds the number of lines of code constant and gets rid of 4 of the 5 engineers.

On the other hand, the company may decide that it really needs all hands on deck. Maybe the company is a standard techco that needs to push out features as fast as possible. In this world, the company holds the number of engineers (that they can afford) constant, and increases the LoC output to 100k per month.

As with all things, the actual answer is likely in the middle somewhere. But notice that any setting of this knob that's not the most extreme option — the one that sets the "lines of code" dial all the way to the max — results in someone being fired.5

Going back to the music industry for a moment, sometimes I think about clarinetists. If you played the clarinet in the 1910s, it was relatively easy for you to provide a middle class lifestyle for your family — the average musician was pulling in roughly half the salary of a surgeon, the highest paid occupation of the time period. Today the average musician only earns $37k. Inflation adjusted, that's almost exactly the same as what the 1910s guy earned. But the average surgeon is earning 10x that.

It gets worse. In the 1910s the census had roughly 139k full time musicians, almost .35% of the total working population. In 2022 the total number of full time musicians was only 37k — already a massive absolute drop, but as a percentage we go all the way down to .03% of the working population.

If you were a clarinetist back before the phonogram really took off, there were a lot of jobs and they paid well. Any bar, restaurant, theater, or dance hall needed live musicians to have any music at all. Now, it's a desert. No one wants clarinetists, because no one needs live orchestra when they can ask the genie in their pocket for whatever music whenever they want. I'd wager that you have way more people able to make music today than you did at basically any point in the early 1900s. But the ability to make a career in that space has plummeted. The barriers to entry have dropped, taste is way more important, and there are only like 3 clarinetists who matter enough to make anything close to a middle class living on taste alone. Sure, every now and then you'll get an Elton John6, but, like, you can't exactly plan for that! This is the worst case scenario for what AI will do to all jobs everywhere, except it’ll be even worse because it’ll happen over like 2 years instead of 100.

On a semi-related note: earlier we talked about what AI did to the graphic design sector. One thing that I didn't mention is that the 'true' artists, the senior types who have been in the industry for a while, are thriving — those guys were primarily valued for their taste anyway, and now that is even more valuable. There's an important pattern there: generally seniority and taste are highly correlated, so we should expect AI to disproportionately hit junior, freelance, and entry level positions. The more senior you are, the more insulated you are, the more you'll benefit.

People on the pro-AI side of the debate argue that the existence of automated general intelligence will massively increase quality of life, and I think history suggests that they are right (again, caveat that it doesn't kill us all). But in the short term, I think we should expect some pretty significant labor shocks and a possible increase in wage inequality.

As for the medium to long term, who knows? In my opinion, the nature of work, all work, will look fundamentally different, and it may look very unpredictably different. A musician a 100 years ago would never have been able to predict Spotify or DAWs; what makes you think anyone can predict what comes after AI?

VI.

I've clearly been thinking about this way too much. I need to touch grass, or at least snow, a bit more.

I'll leave off with a final thought. AI as a technology is highly decentralizing because everyone can use it off the shelf for basically nothing. This is extremely useful for folks who are high agency and high talent. If a lot of people do get laid off, I'd hope to see a significant increase in people creating and running successful lifestyle businesses or startups.

And like I said at the top, there's a lot of information arbitrage right now. If you’re reading this blog you’re probably on the right side of the arbitrage!

Selling AI tools is like doing magic, you get to feel like Willy Wonka. It's a great time to get into the startup game. That is why I'm taking my own advice and am in the middle of starting company number 2. But more on that for another time 😁

For those who don’t know, Jasper is a company that popped up in early 2021, selling marketing copy auto-completion tools to marketers. They hooked into OpenAI in their backend and had a very shallow wrapper frontend. And they had a great sales team.

If an EA game sells $1M, that's a loss. If an indie game made by one dude sells $1M, that dude is probably pretty happy!

In fact hiring Picasso may be detrimental, the cubism may detract from the message

In our music example, it has become a lot easier for people to create beautiful music without ever learning how to read sheet music or even play an instrument.

We're using number of engineers as a proxy for amount spent on engineering talent. Instead of firing everyone the company could decrease salary, but that effectively amounts to the same thing and it's a bit easier to think in terms of headcount.

Yes, I know he’s a pianist.

Thank you for the article! Useful examples from history.

I know this is nitpicking, but you can’t raise up a distribution as shown in your plot. Probability distributions need to integrate to 1, by raising the density at every point it will now integrate to more than 1. What you are describing is that the distribution stays the same, but the proliferation of the indie game industry means that more games are being drawn from this distribution per unit of time.