This is a bit more of a personal article than the ones I usually write. It's one that I have been thinking about writing on and off for the better part of three years. And of course, given everything that's been happening recently, healthcare is again at the top of mind. Honestly, I debated whether or not it made sense to post given that it may come across as a bit too political in the current moment. Still, timeliness is maybe a virtue of its own, and self censorship to avoid the appearance of taking sides is for cowards, and I have a small audience of mostly friends anyway. Also I'm jetlagged from coming back from a wedding in Thailand, so what else am I going to do?

I.

Approximately 3% of the global population have a disease called psoriasis. You almost definitely know someone with the disease. A bunch of celebrities have it — Kim Kardashian is maybe the most famous, but the list also includes golfer Phil Mickelson and musician Art Garfunkle. Psoriasis is an autoimmune disease, generally chronic. Its primary symptom is the formation of inflamed, itchy, scaly patches of skin. We don't really know what causes it. It seems to be somewhat genetic, and seems to have some amount of co-occurrence with other auto-immune diseases like allergies.

Most people who have psoriasis have a small patch of it, commonly on joints like elbows or knees. Easily treated by topical steroids. About a quarter have 'severe' psoriasis, where patches cover > 10% of skin1.

I, unfortunately, fall into the far tail of the curve. In my sophomore year of college, psoriasis covered roughly 50% of my body. It's hard to convey what it's like when one of your core bodily functions just fails. But psoriasis is a very visual disease, so I can at least show you.

When something like this happens, you become hyper-aware of all of the little ways in which your body can fall apart. On average the body is pretty good at pulling out signal from noise, so most people never think about how they aren't itchy. At least, until the 'itchiness' circuit gets fucked up, and suddenly its non-stop 24/7. It really puts into perspective all the little miracles that have to happen for your body to work right.

And there are a ton of knock-on effects when something goes wrong. Around this time I was averaging somewhere around 4 hours of sleep. I lost a ton of weight — went from 155 to 134lbs in about a month. Couldn't really leave my bed. Also I was just, frankly, gross. I would shed everywhere, and like a modern day Jabba the Hutt I was constantly covered in oils and ointments and creams to try and offset some of the worst of it. I would spend hours and hours in the shower, set to ice cold, to try and numb my skin. I became incredibly sensitive to a lot of foods, because eating something as simple as a burger would trigger massive flare ups.

My body was like a finely tuned watch that lost a gear. The whole thing just fell apart.

I think if I was a weaker person I would have become horribly depressed. As it was, I was very much considering how I would have to reorient my life, while lying awake in my bed at 3AM. Probably would have to scrap any dreams of going to Google or starting a company. Would likely have to move back with my parents. Maybe I could become a motivational speaker or a test subject? Would definitely end up breaking up with my girlfriend, the psoriasis was already hard on her and I didn't want to make it harder, and besides I was likely going to be on a different life path. This is something many people without a chronic or debilitating disease don't realize — it fundamentally changes you as a person. You quite literally lose yourself.

It's humbling, having to face pseudo-mortality in this way, and I'm grateful for the constellation of people around me at that time who helped me get through it.

II.

This isn't a story about psoriasis, that's a burden that I have to deal with, everyone has something going on with them and all things being equal I'm ok with my lot in life. This is a story about healthcare. But first I wanted to explain, in visceral terms, why forgoing healthcare is simply not an option for me. Or, alternatively, why I have a lot of opinions about the state of healthcare in the US.

In fall of 2019, I got put on a clinical trial for Skyrizi. Skyrizi is a monoclonal antibody, a miracle of modern science. It works a bit like an artificial vaccine. With a vaccine, you stick some dead or weak disease in your body so that it can produce its own antibodies. With monoclonals, you just inject the antibodies directly. This lets you target specific things that are going wrong, that your body may not naturally target. In my case, it's a specific protein, interleukin 23A. Monoclonal antibodies are pretty safe, and tend to have virtually no side effects because of how targeted they are2.

In order to keep the psoriasis at bay, I have to take Skyrizi approximately 4 times a year, or once every 3 months. The list price of Skyrizi is about $20,000 per dose.

I am lucky in a lot of ways. I'm lucky that I was born in an era where effective monoclonal treatments exist. If I was born even 10 years earlier, my life would be significantly different. And I'm even luckier that I always had the ability to get healthcare. Growing up, I had a family provider with a stable job that offered health benefits. Later, I joined a company that had even better benefits. Later still, I got married to a woman who was also willing and able to cover benefits.

Still, dealing with healthcare in the US is, without a doubt, the most dehumanizing and kafkaesque part of my life. Without exaggeration, I hate US healthcare.

III.

Healthcare in the US is an exercise in indignities.

First, the health insurers.

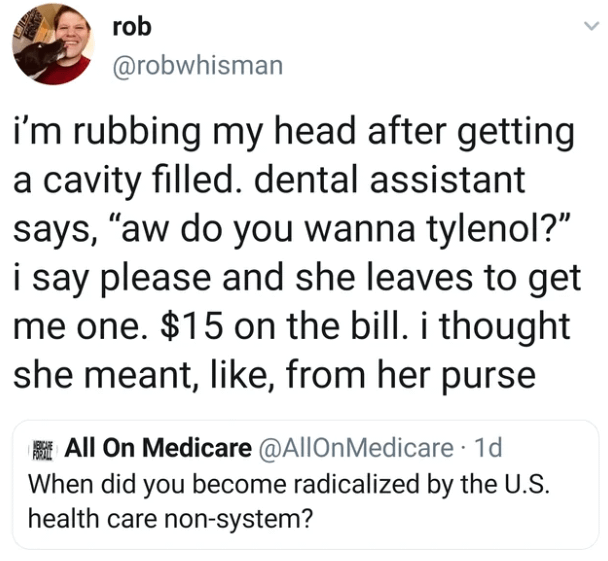

I have to drive for 3 hours every day to go to my dermatologist. I have to get up at 7, get to south Jersey, wait in a waiting room for half an hour, just for some nurse to inject me in 5 minutes and send me on my way. Why? Because my insurance will charge me ~10x more out of pocket if I self inject. No, seriously — if I go to the doctor to get an injection, I get charged $40. If I do it myself, I get charged $400. I asked my insurance provider about this, and they acknowledged that it was strictly worse for everyone involved for me to have to go to my provider. Still. To the provider I go.

Every time I switch insurance, for any reason, I am at risk of missing an injection. Why? Because the insurance will refuse to cover without prior authorization AND a prescription, neither of these seem to transfer between insurers OR between doctors, and the arm of the insurer that talks to the doctor's office does not speak to the arm of the insurer that talks to me. So I will have someone on the line who insists that I am covered and everything is good, only to have the same company tell my doctor that they are denying coverage because I am not on their plan. This takes hours of my life to resolve.

Related: the concept of in-network vs out-of-network is insane. Medical history is a real thing, it's valuable and important to have a single doctor who knows your health inside and out. Every time I switched insurance, I also had to go through the song and dance of making sure all of my current providers were still in network. That's before you get into the arbitrary bullshit of going to an in-network hospital and getting slapped with an out-of-network fee because the anesthesiologist happened to not be covered.

Because I ran a startup, I have the unique insight of being both an employer and an employee. If you think healthcare as an employee is insane, I'm here to tell you the other side is equally bad. Healthcare benefits — really really shitty healthcare benefits, where basically nothing was in network and the deductible was insanely high — cost my company roughly $1.2k per person per month. In other words, I was paying every one of my employees somewhere between 5-18% less per year than I would like to, only for them to have to get hit with multiple-thousand-dollar bills anyway. And setting the insurance up was itself nightmarish. Did you know that small businesses can only provide healthcare if some minimum % of employees buy into it? As far as I can tell, that's not a law, that's just a rule health insurers have. They wouldn't let me pay them for coverage until one of our EU employees came to the US.

Also, just a small straw on the back of everything else, why are insurance websites so uniformly terrible? I have never seen companies with so much revenue have so much web downtime.

Next, the providers.

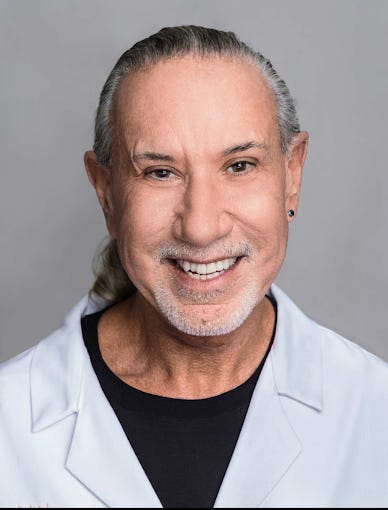

Most doctors are idiots. By 2017, I was more knowledgeable than virtually every dermatologist I met about the nature of psoriasis and several other auto-immune disorders. I'm not bragging, the bar is just really low. These were derms at good institutions! NYU Langone! Mt. Sinai! And still, I would have to walk into the room and explain to them what treatments I needed. They were charging my insurance insane amounts to, effectively, sign a paper after I told them what to do. I am very lucky that I ended up finding Dr. Jerry Bagel, he remains one of the few doctors who knows more about psoriasis than I do. And to this day, I look almost exclusively for doctors that are active in clinical trials or publishing research.

And let's talk for a moment about those insane charges. Here is what my routine Skyrizi injection looks like. I walk into the derm's office. Sign in with the front desk. They charge me a $40 copay. I wait around for 10 minutes in the waiting room. The nurse calls me in, asks if anything has changed, I say no. The nurse gives me my injection. The doctor comes in for approximately two minutes, asks if anything has changed, I say no. He shakes my hand, walks out the door. I go back to the waiting room, schedule my next appointment. I am with a medical practitioner for maybe 5 minutes total, during which time I get an injection that I am trained to do myself and that countless people do themselves all the time. For this, the doctor charges my insurance $400.

The pharmacies and drug manufacturers are just as bad. Creating a monoclonal antibody is not that hard, especially once you've done it once and you have the appropriate cell lines. The up front cost of creating a monoclonal antibody is maybe a few thousand dollars; the marginal cost is maybe a few hundred. As mentioned, a single dose of Skyrizi costs $20k. There's a lot of blame that can be laid at the feet of regulatory agencies like the FDA for making the cost of drug development so prohibitive. But, still. This is nuts.

And this is life post-ACA/Obamacare! Every time I have to deal with healthcare, I thank God I don't have to deal with a nightmare world where pre-existing conditions could be disqualifying or jack up premiums. To the extent that it matters, I refuse to vote for anyone who seriously advocates for removing ACA or for reintroducing separate coverage pools for those with preexisting conditions. Maybe the folks who want to repeal Obamacare don't actively hate me, but they clearly are ok with making my life significantly worse, and as a result I hate them.

IV.

In case it's not obvious, I spend a lot of time thinking about healthcare, even when I am not actively dealing with it, because I depend on it to live my life. I cling to my access to Skyrizi the way a drowning man clings to a life preserver. I cannot go back to a world without this drug. And I cannot pay for this drug on my own. So I am held hostage by the healthcare system. And I want that changed.

I think it's very easy to construct an argument for universal healthcare on humanitarian grounds, so I'm not going to bother here.

Many people have also constructed very compelling arguments for universal healthcare on financial efficiency grounds. A rough sketch of the argument. Having a single payer for healthcare makes it so that providers cannot jack up costs while also streamlining most of the bullshit that comes with the crazy bureaucracy we currently have. This is basic economics — the price of a service is where supply meets demand. If there is only one buyer, demand is entirely monopolized. Any supplier has to play ball with the buyer to stay in business, and the price therefore has to fall to cost + the margin the supplier requires to stay in business vs. doing something else. I think the counter argument is that this will reduce supply because some medical professionals will decide the field is no longer worth it, and go on to become CS people (or something). But we already artificially reduce supply thanks to cartel-like behavior from the AMA, which in my opinion exists solely to drive up salaries for its members. That includes things like restricting the number of residency spots for basically no reason, or preventing talented doctors from other countries3 from practicing in the US.

I tend to lean towards libertarianism, so I also wanted to take a stab at arguing for universal healthcare on libertarian grounds. The crux of libertarianism is the belief that individual freedoms are good. That is, people are the drivers of their own lives, they know what is best for them, and maximizing their ability to choose is therefore an end in itself.

The current healthcare system is profoundly anti-freedom, because it forces tradeoffs between health and self actualization.

As a motivating example, consider my own struggles with psoriasis. If I was ever unable to get healthcare to treat my psoriasis, I would have to dramatically warp my life to accommodate my health needs. I wouldn't be able to hold down a job, even though I love working. I wouldn't be able to live in NYC, even though I love this city. I wouldn't be able to eat the foods I like, or wear the clothes I want to wear. Libertarians feel that the government monopoly of force is coercive; the threat of violence limits autonomy. But nature has force too. It, too, can commit violence. At risk of being dramatic, a chronic illness is a bit like having a gun held to your head. With psoriasis, I have to make certain choices or suffer, and that's not much of a choice at all.

I luckily live in a world where treatment exists. But this doesn't meaningfully change the coercive nature of health, it simply shifts the burden. I have a different gun to my head, one that makes it a requirement for me to have healthcare at all times. And in the US, this is as weird as it is difficult. Consider, for example, what it means to have healthcare provided by an employer. When I was leaving Google to start a company, the main thing holding me back was my fear of not having coverage! I was effectively tied to my job!

If I did not have loving parents with the means to cover me, I would still be at Google4. Once I aged out of my parent's healthcare and moved to COBRA, I had to pay about $1k out of pocket to maintain my coverage. Luckily my startup had already raised funds, so I had a source of income. But it wasn't, like, a lot of income — healthcare cost me 17% of my post-tax income.

I finally ended up on my wife's health insurance. She's amazing, and I love her so much, and we knew we wanted to get married. But healthcare was a significant factor in us choosing when to get married — right before I was about to age out of COBRA. Practically, being on her insurance is fantastic for me. Still, we're both aware that now the gun is on her head. She can't leave her job because it will fuck me up.

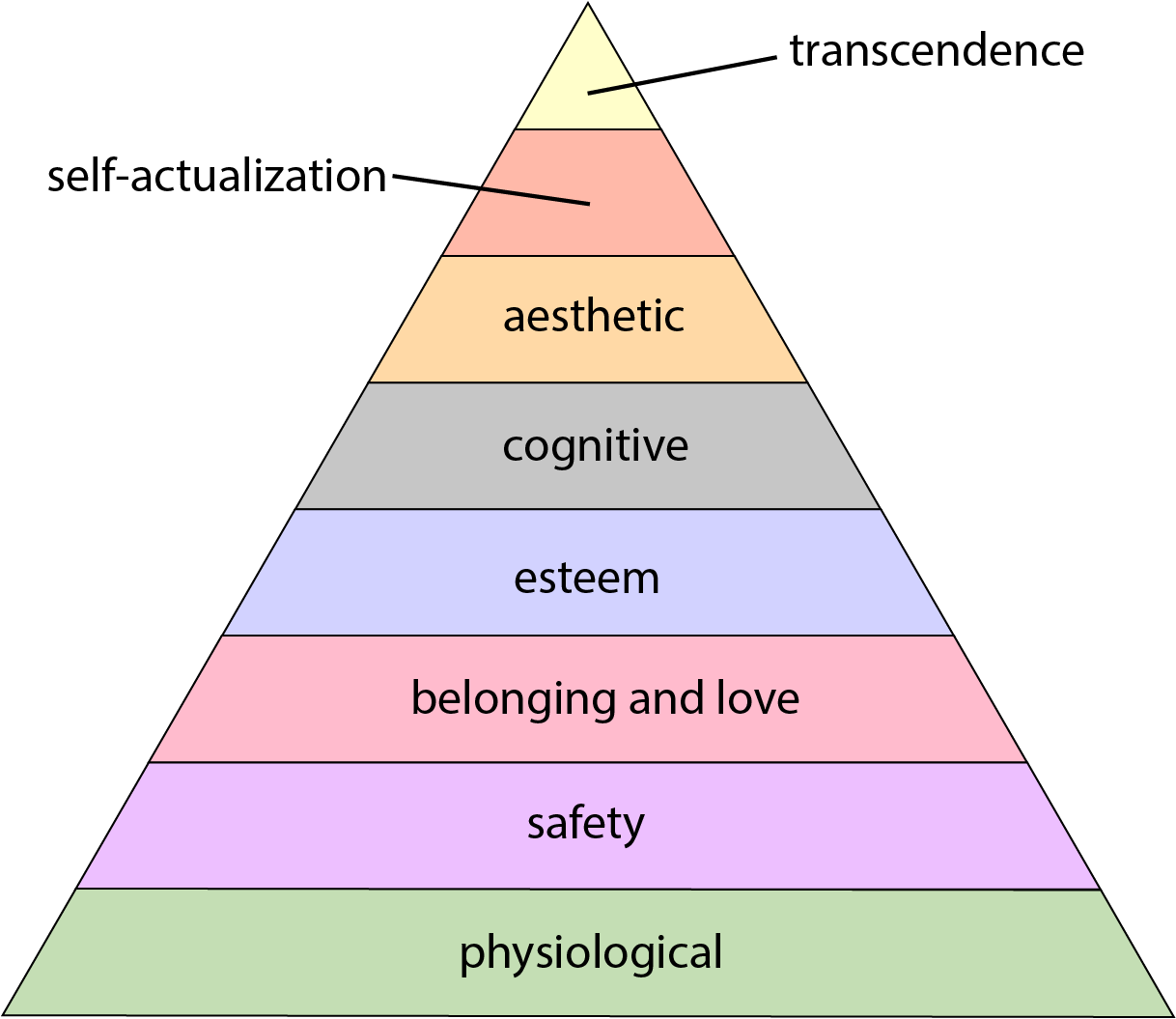

I call this Maslow's curse. Very roughly, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs is a theory of human motivation that classifies needs into categories and ranks them by importance. Each layer of the hierarchy can only be considered if the layer below it is satisfied.

Health is at the very bottom of Maslow's hierarchy. It is a stronger driver of action than self esteem, love, or even safety. So Maslow's Curse is a natural corollary to the pyramid: any risks to health preclude the pursuit of all higher-order needs, rendering aspirations for security, belonging, esteem, and self-actualization irrelevant until the immediate threat is addressed. And this intuitively makes sense — anyone who has ever had a particularly bad headache, or gotten the flu, or even had seasonal allergies, knows that when you are sick, your world narrows significantly. For me, some of my most intimate life decisions explicitly have to take healthcare into account.

This means the healthcare provider and the health insurer are both asymmetrically powerful, even in an environment with perfect information and rational actors. In fact, for someone with a chronic illness, the healthcare provider is often more powerful than the government. Yes, the government can throw you in jail if you don't pay taxes, but the healthcare provider can confine you to your bed, itchy and sore, if you don't pay their fees. The government can restrain you physically but you at least retain your being; the health system can rob even that from you.

In case it's not obvious, I want to make a pretty strong claim here: having to think about health outcomes at all is profoundly limiting, even if you don't have a chronic health condition. Nature is as arbitrary as it is cruel, even the healthiest Olympians can get hit by a car. To a first approximation, this means everyone has to spend at least some amount of time planning for and avoiding negative health outcomes. And even if you, personally, are willing to take risks, the same calculus breaks down for dependents like spouses and kids. There's a lot of ways in which choosing to stay at a stable job for healthcare parallels self censoring speech to avoid being 'cancelled'. There's no law or legislation in play, no threat of police violence or anything like that. And yet, everyone who has to think about their healthcare clearly has less freedom. Removing the specter of health risk is, in my opinion, one of the most pro-liberty actions we could take as a society.

V.

I don't think anyone is seriously defending the current system in the US. But some people might defend the opposite of universal health coverage — that is, a total free for all, no regulation environment.

The argument goes something like this:

Competition in markets drive costs down;

Government regulation limits competition and prevents the free market from doing its thing;

The government has no price sensitivity and so isn't incentivized to cut costs;

The US Government in particular is incredibly bloated and bad at running or supporting complex operations like healthcare.

I think there's a few reasons this doesn't quite work.

For one, the nature of healthcare prevents actual competition.

There's no way to discriminate on prices because they are intentionally hidden from the consumer.

Competition requires an informed population, but it's unreasonable to expect a lay person to know what medical interventions are actually required.

It's true that an unregulated insurer is incentivized to bring down provider costs; they are also equally incentivized to jack up consumer costs while minimizing payouts (and regularly attempt to do this even in our current regulatory environment).

The urgent nature of a solid chunk of healthcare makes it very difficult to be a rational consumer. Bluntly, someone having a heart attack isn't going to check if the ambulance is in network.

For another, in a no-regulation free-for-all there are exactly zero institutional actors actually interested in improving health outcomes per dollar spent.

Public companies have a legal "fiduciary duty" to get the best outcome for shareholders. Many of the largest providers and insurers are public companies.

Fiduciary duty has essentially no relation to patient outcomes; in fact, the opposite is often true. Providers are incentivized to ensure patients are never fully cured. Insurers are incentivized to collect as many premiums and deny as many claims as possible.

To exacerbate things, the average buyer of health insurance is some employer who is also trying to minimize costs.

In a perfect world, everyone would be highly sensitive to bad care. But in practice, insurers and providers can get away with terrible practices for a very long time, because competency signals don't propagate through the market and purchasing is highly inelastic5.

Finally, I think the government actually has a reasonable track record for running healthcare programs! Medicare is super popular, and it seems to significantly reduce administrative bloat! Quoting Paul Krugman:

Yes, American health care has uniquely high administrative costs. But Musk pretty clearly imagines that these costs reflect government inefficiency, when the real reason health care in America involves so much bureaucracy is the exceptional degree to which we rely on private insurance companies. Comparing administrative expenses for public and private insurance is tricky, but there’s no question that they’re much higher in the private sector.

This comes back to the point that running the government isn’t at all the same as running a business. The purpose of Medicare and Medicaid is to pay for peoples’ health care. The purpose of health insurance companies is to collect premiums; paying for care is a cost — the industry actually calls the share of premiums that end up paying medical bills the “medical loss ratio” — and they devote considerable resources to finding ways to avoid covering medical expenses.

But, look, I know I'm not providing a perfect argument. I think there's a lot of other ways you could nitpick. You might argue that single payer has weird edge cases. Or you might point out that health insurers are mostly not the issue, the real problem in our society is the providers who overcharge. Or you may find some statistic that shows that patients actually pay less out of pocket than many other countries6. To which I say: the current system is monumentally fucked up, I am not an expert, and if you are, fix it. I don't care about some nitpicky edge cases. I don't care that it's hard to fix! It should not be my job to care! If I build software that leaks data, or breaks constantly, or that does not do what it is supposed to do, I am held responsible. I can complain that it's hard as much as I want, that does not change the nature of the job. If healthcare were treated like any other industry, the response from consumers would be seething, incoherent rage. And, actually, that's exactly what it is, but thanks to smoke and mirrors there's no one obvious to direct it to.

VI.

Until now.

How could I not talk at least a bit about Luigi Mangione?

At this point a few thousand think-pieces have been written trying to make sense of the assassination of the UHC CEO and the public response that followed. What I see most consistently is that anyone who has spent any amount of time dealing with healthcare is pretty universally understanding. They may not be outright supportive, but, you know, they get it.

I mentioned this earlier — healthcare companies, both insurers and providers, are trying to find as many ways to externalize costs and internalize profits. The business model for health insurance is to eat premiums and pay out as little as possible. This is the structural incentive. Any amount of payout happens because the company thinks it cannot get away with less, whether due to regulation or public outcry.

Brian Thompson was CEO to the largest insurance company in America, a subsidiary to the 4th largest company by revenue overall in the country. The parent, United Health Group, is just under Apple in terms of ranking, is the 9th largest company in the world, and is the world’s largest healthcare company. Thompson has no medical experience. He was never a doctor. He was never even a claims adjudicator or patient advocate. He started at UHC in corpdev, i.e. the people who buy and merge with other companies. And he spent the rest of his time as CFO of various arms of the company. First and foremost, Brian was a businessman. At his level, everything is statistics. If I had to guess, he has never once heard the details of any specific claim that UHC denied, except maybe through the news. And this makes sense — his job was to make the company money.

In some sense, Brian Thompson was structurally set up to do evil, even if he himself was not a bad person. I'm reminded of my review of The Zone of Interest, a Holocaust movie that follows the life of the head of Auschwitz:

In 2024 I think this is a pretty well understood concept, but at the time of Arendt’s writing the 'banality of evil’ concept was pretty revolutionary. Evil was thought to be a really active process, something that relied on the full throated participation of ‘evil people’. It’s a nice fiction, it allows us to separate the world into clean categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ and mete out condemnation and punishment accordingly. But the Holocaust, with its tens-of-thousands of willing passive participants, showed that in reality evil can come from totally common and non-unique sources of motivation. Something as simple as wanting to excel at a job, for e.g.

There are a lot of moments that are literally jaw dropping. Maybe the most visceral is when Hoss is playing in the river with his daughters, only to discover that he is swimming in the remains of corpses that are being dumped up stream. But I think the one that got me the most was when Hoss meets with Topf and Son. To recap, Hoss sits down with these two engineers, and together they pore over blueprints for a new crematorium. They talk numbers. The engineers are clearly proud of their device — it manages to cool one chamber so that it can be cleaned out (of human remains) as the other one heats up (to burn more bodies) in an alternating clockwise system. Efficiency is the name of the game; it never occurs to anyone in the room to question whether being efficient at killing people is a good thing.

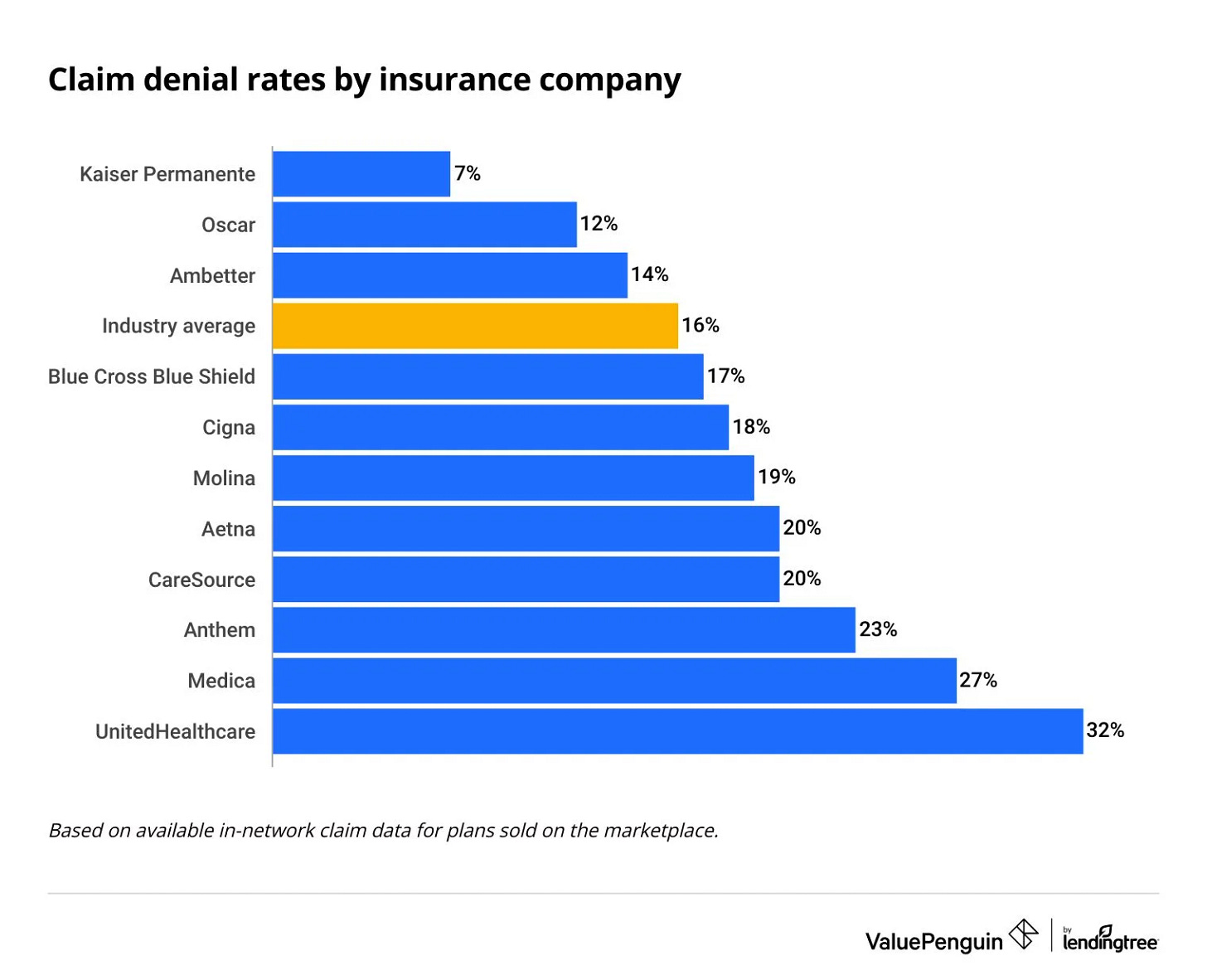

So here. The stats that have come out about Thompson's tenure at UHC are damning. In the 3 years that he was CEO of UHC, the company nearly tripled its rate of denial for prior authorization.

This is, to put it bluntly, why Brian was great at his job, and why he was paid so much to do it. Thompson was likely a good person. Good dad. Good executive, maybe even a good boss. He wanted to do well at his job and by all accounts he succeeded7. But his job was foundationally rotten8.

VII.

I keep going back to this concept of 'what the company thinks it can get away with'. Health insurers and providers are constantly trying to externalize costs. Whatever else, Luigi's actions forced the company to reinternalize some of those costs. They change the boardroom calculus.

Imagine, for a second, how an executive decision gets made at a company like UHC. Maybe UHC wants to trial a specific program — like an AI that auto-denies claims — that they think represents an additional $100M in profit but makes the company 5% more likely to get hit with a $1B lawsuit. The executives will sit around a big table in a nice air conditioned room with some snacks and soda cans, and bring in some data nerds who will tell the executives that the AI is good business. These actuaries are pricing in the profit and the likelihood of winning in court and coming to the simple mathematical conclusion that auto-denial AI is profitable. Importantly, they are not pricing in any ethical considerations or even anything explicitly about care outcomes. It's just the bottom line.

This points to the legal way to force a company to reinternalize costs. Maybe you could figure out how to get a class action going, win a huge judgement. If you could increase the amount of lawsuits, or the amount they pay out, or the frequency that they resolve in the patient's favor — basically anything that may decrease the expected bottom line — you could get the executives in their lofty boardroom to make a different decision.

But of course, this is a fantasy.

There are massive structural disadvantages that prevent individuals or even groups of individuals from navigating the legal system. Corporations hire thousands of lawyers whose only job is to be really good at fighting these sorts of claims in court. They will bury you in paperwork and procedural bullshit, and delay any judgement as much as possible. Worse, presumably you are suing because you are actually a really sick person! So in addition to the crazy legal hurdle, you also have to face being sick, racking up medical bills, and so on. The people who have the strongest claims are also the most likely to just die before they get halfway through the process.

Everything else aside, the UHC assassination has changed the discussion between the actuary and the executive. "The AI that auto-denies claims will make the company on average $50M, and there is now also 0.5% chance that your personal career at this company is terminated after you are gunned down in the street while everyone in the entire country cheers", says the data nerd. Maybe this causes the executive to reconsider!

I don't know exactly what Luigi's motivations were. But I will note that in the immediate aftermath of the assassination and the public reaction, health insurers sure took notice. Many took defensive action by pulling down their executive team pages. And at least one insurer also reversed a policy change that looked like it was going to be supremely unpopular. In a world without Luigi Mangione, that policy would have been enacted and, in a few months, patients around the country would have been slapped with larger bills outside their control.

Now, just to be clear, I emphatically do not support vigilante justice. Rule of law is a critical element of civilization-building. We do not want to encourage everyone to take individual action whenever they are slighted, that way lies madness. And from a more deontological perspective, murder is bad — this is ethics so simple that a 5yo would understand. Still, if Luigi's actions spark enough of a public outcry that politicians actually get off their ass and do something, the net utilitarian outcome may dwarf everything else. Ironically, this too is an actuarial calculus. 95% chance that nothing changes, but 5% chance of massive quality of life improvements to every US citizen? Might be worth it for a sufficiently motivated consequentialist.

This whole situation sucks — violence built upon tragedy, everyone comes out looking terrible. But I’m also cautiously optimistic. In an era of incredible polarization, normal people on both sides of the aisle are finding common ground. I’m hoping that the politicians, all of whom have been suspiciously silent thus far, are taking copious notes. And maybe by the next midterm cycle, healthcare reform will be enough of a no-brainer that we actually see some positive outcomes.

For reference, your hand is about 1% of skin.

Skyrizi is immunosuppressive, and I am significantly more at risk of respiratory diseases. But the increase in, say, sleep quality, more than makes up for any downsides of the Skyrizi itself.

Many of whom end up becoming taxi drivers! Enough that this is literally a stereotype!

A lot of 'gray tribe' folks tend to be both pro-entrepreneurship AND anti-universal-healthcare. But IMO there's a conflict here. The current healthcare scheme is terrible for founders, who have to roll the dice on their health in addition to the usual opportunity costs. And it's actually a double-whammy, because those same founders end up needing to pay for employee healthcare at exorbitant rates until they are big enough to throw their weight around. If I were Marc Andreeson or Garry Tan, I'd go all in on universal healthcare because it would dramatically increase the number of founders!

Let's say UHC board members decide that it would be financially prudent to auto deny every claim. How would the market respond? First, consumers would have to identify that this is occurring. Then, they would have to convince their employers to change insurers. And if that doesn't work, they would have to leave their employers for better benefits. Maybe, eventually, the market might adjust. Maybe employers would realize that they can't offer UHC as a benefit, and would move away from UHC, hurting UHC’s bottom line. But it seems more likely to me that UHC would get away with it for a shockingly long time. I think it would be very difficult for anyone to prove they were auto denying claims. I think it would be even harder to get enough of the consumer market to take it up with their employers, such that this meaningfully pressures UHC at all.

Lies, damned lies, and statistics. This is a bit like Democrats claiming the economy is fine in 2024.

I’m, uh, somewhat purposely leaving out the insider trading lawsuit.

Don’t get me wrong, someone with Thompson’s acumen is incredibly useful for any company, and in many places (tech, manufacturing) he could have done a lot of good. At my startup, we needed people who were able to effectively cut costs and raise profits. But this is further justification that the corporate structure is simply the wrong one for healthcare.

I suffered from pretty bad eczema which has some similar qualities to your condition. Glad you got yours under control. I was saved by Dupixent which I consider a miracle drug, thankfully I can self inject.