i. The Mac line of computers, and Apple products more broadly, are beloved for their simplicity and elegance. They are sleek, with top of the line hardware. They run a well designed operating system. They integrate together with the rest of the Apple ecosystem seamlessly.

Apple is the world's most valuable company. And yet it's generally not the most innovative, in the sense of pushing something really new. They weren't the first desktop — that was the Commodore. They weren't the first laptop (as we currently understand them) — that was the ThinkPad. They weren't even the first smartphone — that was BlackBerry. Apple wins not from being the first mover, but from being the best mover.

Every Apple product has a large price premium, and you could definitely argue that some of that premium comes from its role as a modern status symbol. But I'd argue that a larger part of that premium comes from the experience. Apple spends a ton of man-hours obsessing about the out-of-the-box game feel of their products. They care about defaults.

You turn on any Apple product, and it just works.

There's value in customization. There are tons of people who use Linux or PC. I love Linux because I get to tinker with it and really make it my own. But the simple truth is that no MacBook Pro user ever had to flash their bios because the graphics driver stopped working, or whatever. The simpler truth is that 99% of people don't love computers qua computers. They love computers as a means to some other end. Maybe programming, or graphic design, or surfing the web. And as such, 99% of the population just wants things to work. If you want to go do something weird get a Linux box.

ii. Here's a story of two lawsuits.

There once was a company that was pretty dominant in the tech world. A lot of people were already using their software. The software was good and valuable, and the company was raking in cash as a result. But the company wanted to make sure that other upstarts couldn't appear out of nowhere and start eating up market share. In order to avoid this outcome, the company started bundling their software with other platforms that were also really popular but maybe only tangentially related to the original software. The thought process was straightforward: the software was valuable for the platform because the software was high quality; the platform was valuable for the software because most people using the platform would just use whatever software it was bundled with. It neatly solved the competition problem too. Much harder for a competitor to get traction if no one knows they exist.

20 years ago, this was the story of the Microsoft antitrust suit. Last summer, this was the story of the Google antitrust suit.

Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer with Windows, expecting that approximately no one would download another web browser if they already had one on their operating system. And they were right. NetScape was the dominant browser with 75% marketshare. After Microsoft started bundling IE for free with Windows, IE ended up with a whopping 96% of market share within 4 years, and NetScape was ground into dust.

Google paid Apple a whopping $20 billion dollars per year just to be set as the default search engine in Safari (and to stop them from showing other options during initial setup). And while I couldn’t find the number of people who switch search engines from the default, at least one study suggests that in some parts of the world, Google’s position as the default nets them 20% more traffic than they would have otherwise received.

I'm not necessarily here to litigate those antitrust cases. I'm more interested in how we think about the "default settings". In both cases above, the tech giants realized that the average user didn't care for customization. And as a result, being the "default" software was really really valuable. You could switch to some other web browser or search engine. But, you know, you probably wouldn't care to. You aren't using those things out of some ideological commitment, they are tools that represent a means to an end.

There's a lesson here: if you are a big company selling a product, it's in your best interest to become the "default" way things get done. And in fact, you probably want to pay a really high premium to do so — maybe $20 billion worth.

iii. I think a lot of folks who work in software and build products spend a lot of time thinking about defaults. It's UX design 101.

But "defaults" aren't just important in software, they show up all over the place. Cars drive on the right side of the road. Refrigerators and washers and air conditioners have standard out of the box settings. Light switches default to "off" when flipped down.

Sometimes defaults are created by legislation. The government mandates that you pay for tolls and gives a lucrative contract to EZPass to implement a digital payment system. Now EZPass is the default, and you have to use it if you want to pay tolls without stopping on the road.

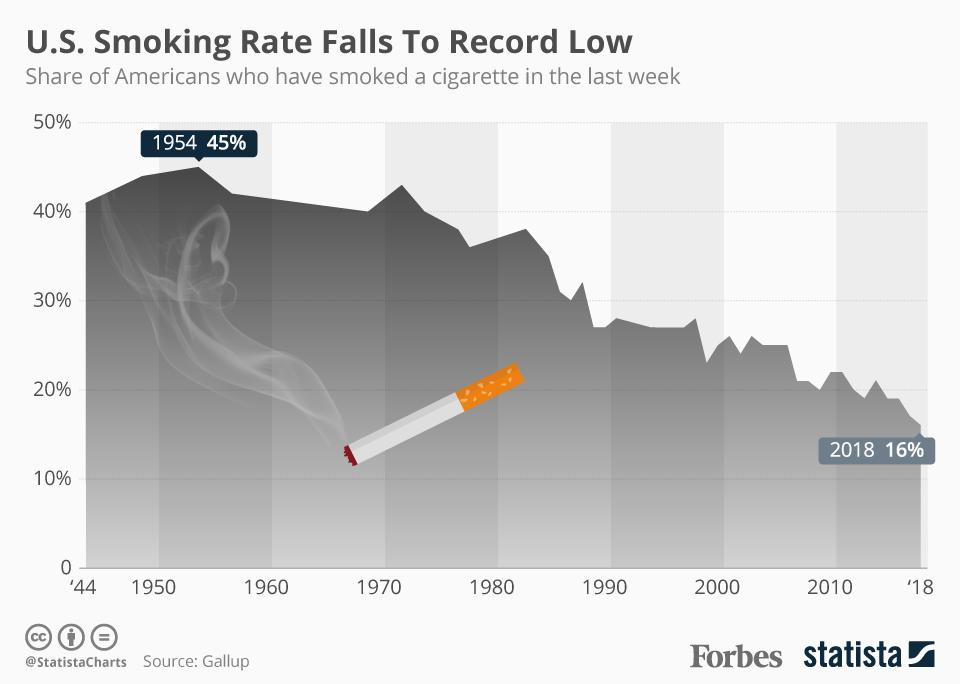

Sometimes defaults are created by social pressure. For a long time, the default expectation was that you would smoke. Smoking was omnipresent in bars and restaurants, movie theaters and opera halls, homes of every kind. Everyone smoked. So the default was that you, too, would smoke.

As a society, there are all sorts of implicit and explicit rules that guide what we do — a set of societal defaults. And most people don't care about most of those default settings most of the time. But just like in any product team, everyone has a strong opinion about some part of the default settings.

iv. One way to think about politics is that it's a struggle for who gets to set societal defaults, and what they should be.

Generally, in the US, we opt for local defaults. Individual towns/counties/states can set their own defaults. Some of this is legal (taxes), some of this is social (food), sometimes it's a mix. The flexibility allows for both self determination and self selection.

But sometimes, we really do push for country-wide defaults. Unsurprisingly, this is where the most polarization and conflict lies.

It's tempting to think of defaults as "things that are legal or illegal on a federal level", and I want to caution against that interpretation. When we think about defaults, we should be thinking about smoking, and how it went from something everyone did to something no one(ish) does. In the 1800s, smoking became a default thanks to the marvels of mass production hitting the tobacco industry. Then, through the mid to late 1900s, there was a massive political fight that took place on every level of US society to try and change the default behavior. And by the early 2000s, not smoking was as natural as drinking water.

The defaults of society are the things that people aren't even questioning anymore because they're so ingrained, even if they were once deeply political fights. Things like two day weekends (and the general concept of workers rights), or the abolition of slavery (and the general concept of civil rights). The only way to change a default is massive amounts of sustained pressure, so being a societal default is valuable in the same way being the default search engine on Safari is valuable.

In some sense, all of the political fights today are about trying to become the defaults of tomorrow. Gay marriage is most of the way there. Other hot button issues like abortion, DEI and affirmative action, schooling, health insurance, trans rights, and gun rights are still up in the air.

In 50 years our children's children may look back at how we approached any of those topics with the same naive incredulity that kids have today when they think about smoking and non-smoking zones in restaurants in the 70s. It's just, you know, we don't know from which side they'll be looking at it all.

v. Society is not a company, we aren't building a product. But there are some ways in which the model is useful. The average user of a MacBook is not particularly technical, not particularly smart, not particularly engaged, not particularly anything. The challenge of the Apple Product Manager is to thread the needle for the average person. What leads to the best outcomes for the most people?

Generally, the best UX is sane defaults that enable 99% of things, with off ramps to more customization1. The MacBook does mostly everything right, but you can still customize it a bunch of different ways if you want. Not enough? If you zoom out a bit, you can pick up any of a million PCs or Linux machines for roughly the same feature set and way more customization. Still not enough? Get a framework laptop.

If you squint a bit, the same thing kinda works at a societal level.

Public education is maybe the most obvious example. As a society, we offer a baseline amount of education and childcare. It's not perfect, there's a lot of debate about what is appropriate, but everyone gets the default and then people who feel strongly about it can go private or charter. Food and drug regulation is another example — generally you can assume that the groceries you buy have a certain baseline level of safety, and if you want non-gmo organic supplements or whatever you can do that. For a more controversial example, people seem to really like German healthcare, which is a mix of a strong government sponsored universal care system upon which you can layer all sorts of (more expensive) private options.

Even though I tend to lean libertarian, I like this setup. As a society I feel like we often screw up by assuming that the defaults are the best for everyone and then hamfistedly barring any alternative. The defaults aren't going to be perfect for everyone, they can't be. There's just too many people. But as long as there are viable, valid off ramps for a wide range of customization, it's fine! People can price how much they value something accordingly.

On the flip side, some libertarian types go wrong when they argue that we shouldn't have any defaults at all. They don't realize that this too is a default by a different name. You can buy an iPhone that's just hardware and personally flash every bit of firm/software onto the machine. But, like, this would rightfully be seen as a very fringe thing to do, and making that the only option just devalues the whole experience.

Still, the very nature of setting defaults means some people will have their 'costs' covered by society, while others will have to 'pay' to follow their preferences. It may seem coldly utilitarian, but I think a reasonable approach to setting societal defaults is to aim for whatever is most beneficial for the most people with the least amount of customization. You have to start from the assumption that most people don't care about any specific policy, and won't spend time going out of their way to do anything besides the default thing, and then work backwards from there. What is the best outcome in that regime?

vi. So anyway, this is actually a post about water fluoridation.

It seems like RFK Jr. is the incoming nominee for Secretary of Health. Lightly put, he is a very strange man. His Wikipedia page reads a bit like an unmoderated Reddit thread — unpredictable, occasionally alarming, and never quite what you expect. That overall vibe extends to his team's more recent policy statements, which has been pushings things like removing approval for the polio vaccine2.

Even though it seems kinda obvious to me that RFK is an actor of questionable repute, some number of people have come out of the woodwork to support one of his other strange suggestions — removing community water fluoridation.

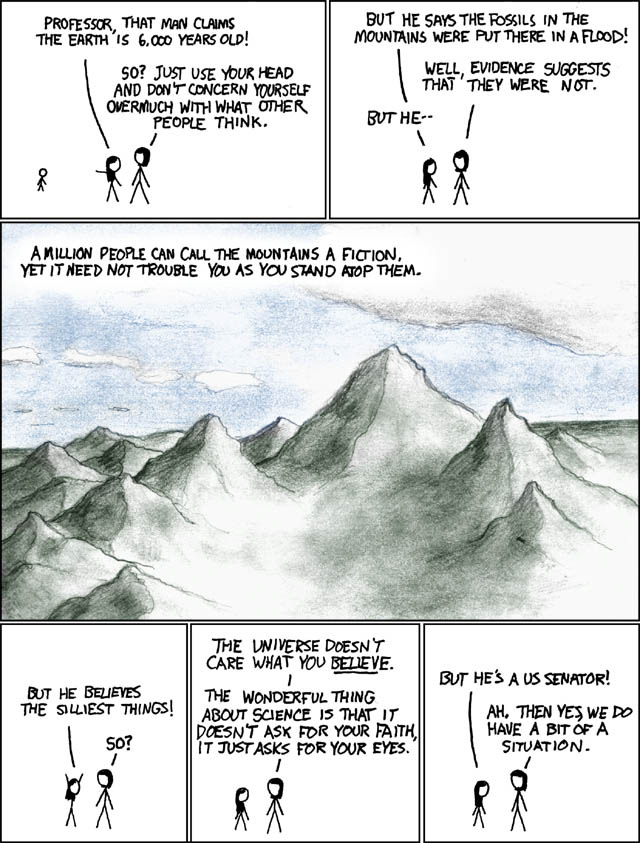

Now, as a brief aside, the fact that anyone is taking anything this man says seriously is a bit baffling to me. Don't get me wrong, I appreciate steelmanning as a method of truth seeking. But, well… imagine you encountered a schizophrenic guy on the subway, talking about chemtrails and cell phones being used as a means of government control. Literally tinfoil hat stuff. You might feel a bit justified if you didn't immediately jump to do deep research about all of his other claims. In fact, you may be a bit confused when some other people you know, ostensibly smart people, start talking about how "we should really look into this lizard people thing, the guy on the subway said it could be weird". This is how I feel about the current state of the fluoride debate. Yes, it's possible that a broken clock can be right (though I think in this case it isn't), but I worry that this is somehow legitimizing all of the other crazy things RFK says, most seriously about vaccine policy3.

Still, let's do the thing I'm saying we shouldn't do and talk about these proposals somewhat seriously. We sorta have to, since he's going to be SecHealth regardless.

We have a ton of empirical data on the impacts, both positive and negative, of water fluoridation. And there's a lot of really good meta-analysis that you can just read on Google Scholar. A lot of the concern seems to be about the effect of fluoride on IQ, so I'll focus there. From my own reading, the consensus seems to be:

fluoride in water appears naturally in many places;

about 60% of Americans get fluoridated tap water. The federally recommended dose is 0.7mg/L, and actual quantities range from 0.7-1.2 mg/L;

water fluoridation definitely and massively helps reduce cavities (somewhere between 25-60% decrease in cavities);

at 25-100x recommended levels, fluoridation can definitely cause problems in bone structure and developmental IQ;

at > 2x recommended levels, there's consistent evidence of small IQ decreases in children and not much else;

at recommended levels, there's no indication of risk of basically any kind. This is partly due to the lack of studies at the lower range (most studies measure outcomes at 2mg/L or higher).

I think the best systematic review on fluoride's effects on cognition is from the NIH here, which is also roughly what I’ve summarized above. An earlier broader review of all fluoridation effects is from the National Research Council here. For the rest of this article, let's take the NIH position as mostly true.

vii. Because fluoride is in the news, some of the smarter folks on the web have come out against water fluoridation. That's their prerogative. But they also have been making some arguments that I find questionable4.

First, they say that folks can always add fluoridation to water if they so choose.

Second, they say that not having any fluoride in water is the default choice, and people shouldn't be forced into a medical decision they don't agree with.

I think both of these arguments are really subtly wrong, and it's easy to miss why.

Water fluoridation is maybe the most default default I can think of. Very few people think about tap water in the US. In the major cities, drinking tap is a given. In rural areas, thought begins and ends with 'do I need a filter' or 'is it "safe" for some arbitrary definition of safe'. For the most part, people follow whatever the guidelines are for wherever they live without much additional thought. I personally only just learned that my town does fluoridate, even though most of the state I grew up in doesn't.

And honestly, it is super reasonable to not know this. Most people have their own things going on and wouldn't have the time or interest to understand the minutiae of water fluoridation — assuming they could deeply understand the pros and cons to an expert level anyway. Given that this is the case, we have to assume that any policy decision is essentially going to be taken up without further thought by the majority of the populace. There's very little 'customization' here. And that in turn means essentially no one is going to be manually adding fluoride tabs to their water. Or, put another way, the anti-fluoride crowd could just as easily buy some nice filters and side-step the question on the personal level entirely. The main players in the debate represent tiny tiny percents of people. Assuming one side or the other on face by arguing that the other has viable alternatives is simply begging the question.

Given that any guidelines are essentially going to be mass adopted, which are 'correct'?

"Don't set policies that force a medical choice!", says the anti-fluoridation crowd. Let's say we choose not to set any guidelines and just drink whatever water you have in the ground where you live. I get why this is appealing — this is the most passive option, there's no decision explicitly being made. But, in my opinion, this is maybe the only answer that is obviously wrong. Contrary to expectation, the default option is definitely not 'no fluoride'. Ground water has really variable fluoridation levels, ranging from ~none to above 10 mg/L, i.e. well above where it's a problem. And more generally, we treat water to make it safer all the time, for a wide range of things beyond fluoride. No one seems particularly upset that we get rid of pathogenic bacteria. So in order to get to the 'no fluoride' amount that the internet commentariat seem to be arguing for, we need to make an active decision to modify fluoride levels anyway.

So we basically have to bite the bullet on setting an explicit default. Which just brings us right back to the original question of what the default should be.

The messy reality is that it’s about trade-offs.

It seems like there are basically two options. You could either remove fluoride entirely, as per RFK; or keep fluoride at low levels and possibly incur some unknown risk, as per our current regime. The former comes with a significantly higher risk of tooth decay and all that entails. The latter comes with some possible minor neuro-developmental risk for newborns. Different people are going to fall on different parts of that spectrum, and I think it's reasonable to have different opinions — this is why water fluoridation is mostly locally legislated.

The worst thing about this debate is that there is some legitimate research here that is essentially going to be a casualty of war. The developmental IQ studies are worth following up on, especially if we can just educate the general public about the specific edge case for pregnant women. But it's getting totally drowned out by people who are conflating or mixing that work with fluoride toxicity5, as well as a million other unrelated conspiracy theories.

Still, my own bias is pro fluoride. There’s really good evidence of positive effects on oral health. There’s mixed to no evidence of negative effects at the recommended fluoride ranges6. The population that has any likelihood of negative effects at all — pregnant women and young kids — are a fairly small sliver of the population who have a lot of other lower-hanging risk factors and who already are encouraged to limit or avoid certain foods and drinks (alcohol, raw fish, cured meats, whatever). And all of the stats and studies aside, I think if you come from a high socio-economic status background, where brushing teeth and going to the dentist are obvious things that you should obviously do, it's easy to forget how bad tooth decay can be. You haven't really interacted with folks that are unable to eat carrots because their teeth are falling out7.

More generally, it's important to remember that things like water fluoridation policy mostly impact people who don't care about the policy, and so any opinion is going to be utilitarian-paternalistic. If you're someone who cares a lot about fluoride, you either already have a filter, mostly drink bottled water, or have fluoride tabs you're manually adding to your drinks. Maybe that's inconvenient, but you have all the options available. The people for whom the policy really matters are all the people who don't pay attention to the fluoride debates, either because they can't afford to8 or because they just don't care. In other words, the people living life on default settings.

And the customization is really optional, depending on the maintenance cost of those features against the market size of people who care.

I’m not sure how much I should attribute the actions of RFK Jr.’s lawyer to RFK Jr. himself, but I don’t feel too bad about this link because RFK has historically been on record as pretty against all vaccines. Still, polio? That’s like the one vaccine that basically everyone thinks was fantastic!

Also, as an aside to the aside, why fluoride? It's a bizarre fixation, a bit like the ivermectin thing a few years ago. It feels like it's totally out of nowhere, a masterclass gish gallop, where people now have to methodologically and scientifically refute the rhetorical equivalent of noise.

There's a lot of questionable arguments, actually. The fluoride thing seems to have been picked up by the 'trad' movement, which, uh, is not particularly well known for making good empirically grounded arguments about things. But I’m going to focus on the ones that are at the border of being reasonable.

I.e. poisoning by fluoride intake. This never happens from drinking water, you'd die from the water itself before you died from the fluoride

I would definitely update this opinion if studies showed meaningful IQ drops — maybe like 2 points or more — at the recommended 0.7 mg/L level.

There's a lot of equally good studies on the impacts of cavities on a whole host of negative outcomes. And cavities themselves are quite painful, and dental work costs society billions. Somehow this never really comes up in the discussion, which is weird given that supposedly we care about overall health outcomes.

I don't have any numbers to back this up, but my strong hunch is that this group has much lower hanging fruit than water fluoridation as the primary neurodevelopmental risk anyway.

Sorry but this just seems crazy, unless its some meta thing where you accept your societies default of considering fluorination a reasonable thing to do.

Firstly, I think youre really underestimating the difficulty of opting out. The basic problem is that if you consumed too little fluoride somewhere, you can easily make up for it by supplementing, but if you consumed too much, thats kind of it. And water is in lots of things. So you have on the one hand, swallowing or dissolving a tablet sometimes (or realistically, just brushing your teeth, because theres no benefit to fluoride if youre already getting it from toothpaste), and on the other hand, insane levels of off-griding.

Secondly, while we do manage all sorts contents in water, I dont think thats a good reason to add fluoride. The rationale used here, "We think this is an effective medication that everyone should be on" is in fact very different from how those decisions are made so far. Do note that vaccines that are far more beneficial than fluoride are not mandatory, and *far* easier to avoid - Youre setting up a system where how much pressure we apply in favour of something is basically unrelated to how good it is, and depends only on technical details.

Thirdly, something that noone thinks about either way is not a good default. A good default is one you dont have to think about, but would have to if it were different. If noone thinks about it, you have to make up your own criteria for deciding what the right default is - but this decision draws no legitimacy from the silent majority.