Towards a language for optimization

Can we draw insights from optimization problems in different fields to create a general account of how complex systems work?

Note: let me say up front that I am not an expert and it is very likely that I am missing important literature. Feel free to link things that may be relevant in the comments, and apologies in advance for pissing everyone else off!

I spend a lot of time thinking about optimization problems. This is probably just one of the requirements of being an ML researcher. The funny thing is that when you start thinking a lot about optimization problems, you begin to see them everywhere. Often they share similar patterns. For example, Anthropic recently discovered that deep neural networks represent features in a way that is very similar to how electrons organize themselves on a sphere. Two completely different domains with very similar results. The only thing they share is that both neural networks and electrons on a sphere are subject to optimization pressures.

This is fascinating. But it also points to something that is very frustrating. Even though we know of many optimization problems, and even though optimization impacts us on a very deep level — the economy is an optimization problem, and evolution is an optimization problem, and many physical systems are optimization problems, and and and… even though optimization impacts us everywhere, we do not have a great language for these things.

Here’s a basic example. I have a neural network with some kind of architecture, trained on some kind of data, with some kind of loss function. What happens if I change the loss? No idea. What about the architecture? Well, there’s some opinions, but formally, no idea. What about the data? You guessed it: no idea.

We do not have a systems level way of thinking about these problems. We know how to model a single neuron, and even entire matmuls (!), but we cannot say with any confidence how these things work at a higher abstraction.

I don’t have any extensive answers to this. I’m first and foremost an engineer, and I lack the formal math background to produce something like A Mathematical Theory of Communication but for optimization. Still, I want to take a hodgepodge of some 10 months of notes and turn it into some directions and observations that may chart a course towards a more general language of optimization. Let me note up front that I am not an expert in most of the things I am talking about here, and I am likely missing a lot of preexisting literature. Please feel free to link relevant papers / articles in the comments!

What is a “systems level way” of thinking about optimization problems?

For our purposes, we can be pretty vague about what a system is: a system is basically anything. A car is a kind of a system. So is the weather. So is traffic. Wikipedia says that a system is “a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole.” But everything is composed of other things, so basically anything can be thought of as a system.

Systems thinking is a framing mechanism to help understand how parts of a system interact with and influence each other to produce system level behaviors. Instead of thinking of the system as a set of individual parts that each can be understood independently (cf mechanistic interpretability, Can a Biologist Fix a Radio), we think of the system as a whole. The constituent parts of the system are defined primarily by their relationships to each other, rather than any of their internals.

Systems thinking requires making things simple. When thinking about systems, you have to hide complex internal behavior so that you can reason about higher level behavior. For example, if I was fixing a car, I don’t need to really know about the rubber vulkanization that led to the tires. Or if I was defining a web system, I don’t really need to know how a specific database might implement a caching algorithm.

You can think of this as reducing resolution. You are retaining the relationships and components necessary to understand macro level behaviors, while hiding implementation details.

This begs the question: what information is important to keep, and what is implementation detail? There is an entire subfield of information theory that attempts to answer this question. You can get very deep into Kolmogorov complexity and sophistication and entropy and code books and a whole bunch of other things. If you’re interested, check out my review of the complextropy paper.

Ilya's 30 Papers to Carmack: Complextropy Redux

This post is part of a series of paper reviews, covering the ~30 papers Ilya Sutskever sent to John Carmack to learn about AI. To see the rest of the reviews, go here.

But for this post, we can just say that the most important bits of information about a system are the things that most uniquely identify that system. And this definition is recursive. Something that uniquely identifies many computer systems is the relationship between servers and clients. Something that uniquely identifies a server system is whether or not it has a database. Something that uniquely identifies a database is whether it is a SQL or nosql database. Etc etc.

Here’s a conjecture: any description of a system short of the system itself is tautologically equivalent to defining what is or isn’t important. Anything kept in the description is important, and anything left out is implementation detail. So when someone draws out a box-and-line diagram, they are implicitly making a claim about what is or isn’t important for understanding the system itself.

Another conjecture: any description of a system short of the system itself will drift from the system’s true behavior at the edges. Systems thinking is not about perfectly modeling behavior. You can’t perfectly model behavior, otherwise you’d just be exactly describing the entire system! When you compress information about the system, you lose some detail. That means your summary will not be able to capture the nuances of everything your system does. But that’s ok — the whole point of a summary is to reflect the most important pieces and leave out the things that have less impact.

To build a systems level approach to thinking about optimization problems, we need to understand what bits of information most uniquely identify different kinds of optimization problems. And then we need to understand how those pieces of information impact each other.

Physics as a model for systems thinking

To build a good approach for understanding optimization, we should look at the folks who are experts at systems thinking: physicists. To a first approximation, physics is all about systems thinking. The purpose of much of physics is to boil down the complexities of our universe into a few small highly compressed representations.

Consider the ideal gas law, PV = nRT. Gasses are composed of millions of atoms bouncing around in space. Each atom has a location and a direction and a velocity and an acceleration. To accurately and perfectly describe a mol of a gas, you would need zettabytes of data.1 The ideal gas law takes all of that information and summarizes it into a relationship between pressure, volume, temperature, and substance quantity. 4 floats and a constant. So ~20 bytes. As a compressed description of a complicated system, the ideal gas law is extremely efficient. There are a few places where this law doesn’t hold, where the abstraction breaks down at the edges and you have to peek a layer deeper. But that is mostly in strange edge cases like extremely high temperatures or at phase transitions. The ideal gas law is useful and predictive for a huge range of real world tasks. I’m not sure if this is formally proven, but I also feel like those 4 variables / 20 bytes are often the most significant bits that we care to know about any given gas.

Newtonian mechanics is another familiar example of physics as systems thinking. Newtonian mechanics takes the extremely complicated interactions between objects and turns them into a few simple rules related to mass, gravity, and motion. It wasn’t easy to derive Newtonian mechanics. Newton had to come up with an entirely new kind of mathematics (calculus) to formally express the physical systems he was describing. But the result was, again, an exercise in compression. Before Newtonian mechanics you would have to dive deep on the physical properties of a substance in order to explain how it interacts with other things. You would somehow have to capture the size and shape, the surface material, the density and weight. And you would have to do this in an N^2 way, meticulously describing each object’s interaction with every other relevant object. With Newtonian mechanics, you only need to describe a few key parameters like mass, velocity, and acceleration. We know that Newtonian mechanics break down when things get very very big (black holes) or when things get very very small (quantum mechanics) or when things get very very fast (relativity). But that’s ok, because Newtownian mechanics is still extremely relevant in a very large band of real world use cases.

How do physicists come up with such powerful and efficient descriptions of systems? There is a common pattern:

They start with mountains and mountains of empirical data. For the ideal gas law, this was meticulously tracking the behaviors of gasses in a bunch of different settings. For Newton, this was a ton of observational data about planetary movement stretching back to Galileo.

They come up with an equation or set of equations that fits the data. These equations depend on terms that are real-world relevant. Errors or offsets are mapped to constants — for example, R in the ideal gas law, or G, the gravitational constant when calculating gravitational force.

They attempt to predict other (empirically measurable) behaviors that ought to fall out of their descriptions. How do previously uncatalogued gasses behave? Can you make accurate predictions about, say, the motion of pool balls?

They iterate. If constants aren’t truly constant, if each prediction is slightly off and requires a slightly different error term, they look for other patterns that can explain the discrepancies. This is how we ended up with the van der Waals equation or special relativity.

I’m eliding a fair bit. Gravity is a nontrivial invention, an inspired leap of reasoning. So is calculus. Still, this loop is the engine that has driven our understanding of the physical world over the last five hundred years.

Systems thinking and Optimization

Can we run the same “physicists loop” to come up with ‘rules’ for optimization problems?

Optimization is, by its nature, a very empirical field. There are rarely closed form solutions to most optimization problems. If there were, we wouldn’t need optimization techniques! Many optimization methods depend on various forms of numerical analysis. In some sense, being empirical is in the blood. Yet I get the sense that there has not been much effort to empirically observe how optimization problems behave as a class.

As I write that sentence I feel the need to caveat (I can feel the math folks getting mad at me). There has been an immense amount of work attempting to formalize optimization problems. Convex optimization (very roughly, how do you find the bottom of a bowl) is perhaps the field with the most ink behind it. More recently folks have spent time attempting to understand how loss functions lead to different geometries (remember, deep learning is just applied topology!), how systems behave with multiple simultaneous objectives, and how different kinds of optimizers behave on different problems. The Wikipedia page for optimization is quite large and detailed. I had the distinct pleasure of working with some bona fide geniuses who could think through optimization problems that I had no chance of even understanding. And I also recognize that some of this is simply question begging — we do have analysis and pattern recognition, who am I to say that these aren’t sufficiently low resolution?

And yet…

Even when we talk about convex optimization, much of the work is about process bounds instead of relationships between tunable variables. No ideal gas laws. I recognize that there are vast tracts of mathematics that I haven’t studied that may have the kinds of clean relationships that I’m looking for. But I certainly feel like anecdotally my ~decade in the space has not yielded much beyond “o, everyone is sorta operating mostly on intuition.” In my opinion, we haven’t really managed to get breakthroughs that map to easily understood and productive rules, at least at a high enough granularity. Our ‘systems level understanding’ is still too in the weeds.

Neural network scaling laws

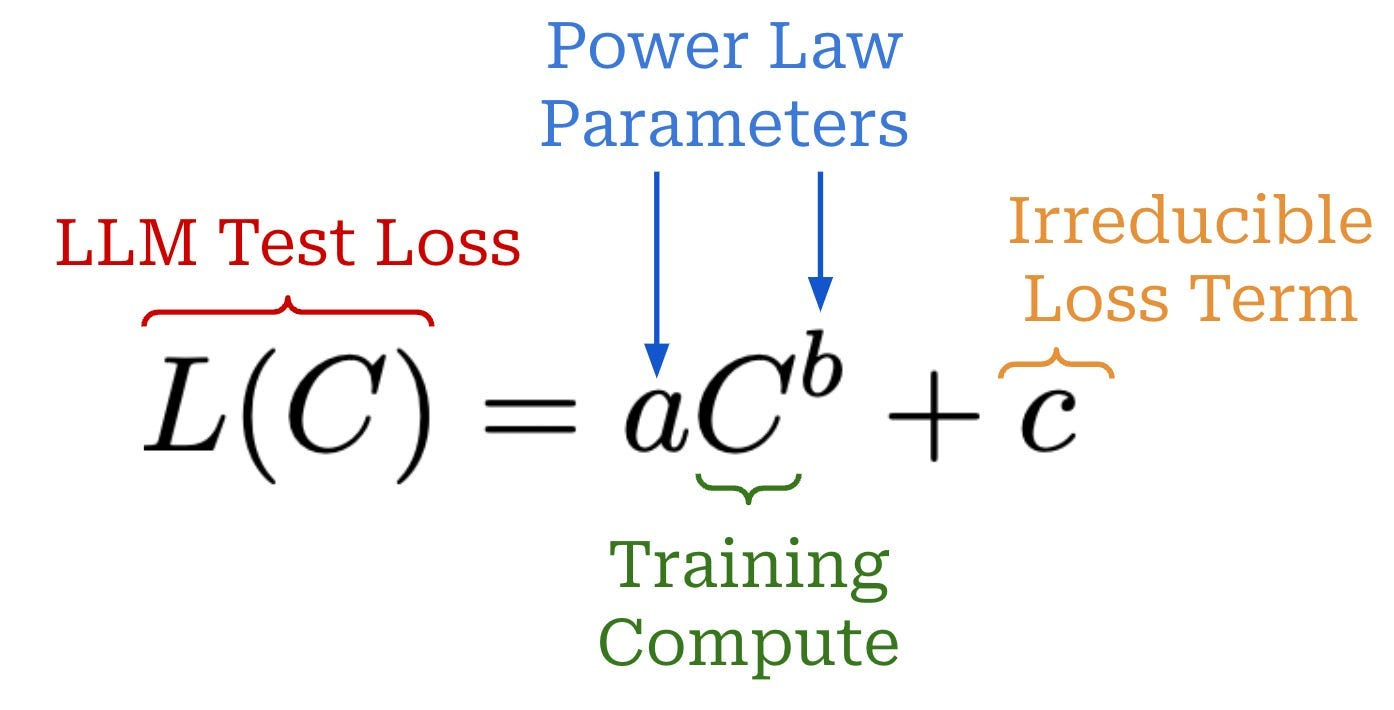

There is one area that I’ve observed where we do have a very good systems level understanding (yes yes, question begging) of a relevant class of optimization problems: scaling laws for neural networks.

A neural network is, as the name suggests, composed of many neurons. We have a very good understanding of how any given neuron behaves. But we have a very poor understanding of how neural networks overall behave. This is in part because most of our leverage is not at the individual neuron granularity. There are very few deep learning experts who are isolating and modifying single neurons in a model. Rather, people think about higher level concepts. We think about architectures instead of individual neurons. We think about datasets instead of individual data samples. We think about a generalized pool of ‘compute’ instead of individual chips or flops. And we think about general model behavior over an entire benchmark, or even multiple benchmarks, instead of looking at individual results. Neural networks are exactly the kind of place where systems level thinking would be very helpful.

If you squint, you should already be able to see the shape of some kind of ‘law’ here. Is there a relationship between model size, compute, dataset size, and performance?

Ten years ago, we did not have a good answer to this question. We simply did not have the empirical data. But in 2020, on the back of the release of the original GPT series, OpenAI published a paper titled Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.

This is an extremely important paper, and it is the last paper in my “Ilya’s papers” review series.

Ilya's 30 Papers to Carmack: Table of Contents

In 2019, Ilya Sutskever (former Chief Scientist at OpenAI and one of the leading lights of the ‘Google Brain’ AI era) sent John Carmack (computer scientist extraordinaire, created Doom) a list of ~40 papers to learn about AI.

I will do a more full length treatment of it soon. For now, the basic gist is that the authors applied the ‘physicists process’ to neural nets. They trained a bunch of different language models across several magnitudes of compute and several magnitudes of dataset size. They tried to fit what they observed to a set of curves. Then they trained new models and checked if their new models also fell on the curves they predicted.

This worked great. In fact, it worked so well, it created a new kind of paper: the ‘scaling law’ paper, where researchers attempt to discover similar behaviors in a wide range of tasks and architectures. It turns out the findings replicate. The relationship between performance, compute, data, and model size is some kind of universal behavior — a power law modulo a constant. All of the complexity of neural nets, boiled down into 5 floats.

I can’t stress enough how useful this systems level understanding is. It directly informs macro strategy. Why was everyone trying to get compute in 2023/2024? Because the scaling laws said they were bottlenecked by compute. Why is everyone trying to get data in 2025 and likely into 2026? Because the scaling laws say they are bottlenecked by data. Every lab is trying to get the best model performance possible. And it turns out there’s a neat equation that directly maps <things you can change> to model performance. Of course the scaling laws will influence macro strategy!

Some people go so far as to say that architecture doesn’t actually matter, and that any neural net architecture would follow the same scaling law behavior. I’m uncertain. The scaling laws aren’t perfect. They do not capture all the variation. That constant value I mentioned isn’t so constant. It changes a lot based on the architecture and the task. This is why multiple people can publish multiple different scaling law papers. There is some additional underlying structure that we haven’t yet figured out.

But still. The scaling laws are a great example of useful systems thinking in optimization.

Optimization problems in disparate fields

Most of my experience comes from deep learning. But like I said earlier, optimization appears all over the place. Are there other fields that have found ways to systematize complex optimization patterns?

The obvious places to look are economics and biology. Both of these fields deal with systems that are subject to optimization pressures at multiple different levels. Frameworks like comparative advantage or evolution simplify extremely complicated and dynamic relationships. Also, and I mean this in the nicest way, the average molecular biologist and maybe even the average economist is likely not as mathematics oriented as the average computer scientist who works directly on optimization problems.2 As a result, these fields as a whole are less able to lean on theoretical advances and are counterintuitively more likely to make progress by creating useful high level principles. Some of these principles may be applicable across domains, especially if they prove to hold across many different kinds of optimization problems.

Here are some observations.

Thomson’s problem

We already spoke about how Anthropic discovered that the structure of feature representations in the hidden layers of a neural network mimic the behavior of electrons on a sphere. Did you know that viral capsids have the same structure? The current theory for why this structure exists is that it maximizes (there’s that optimization word!) the volume inside the structure. There’s a general rule here: repulsion optimization pressure will always generate Thomson-problem-like geometric structures. And I think there’s a corollary: whenever you see these geometric structures in ‘the wild’, they are likely caused by some sort of repulsion optimization pressure. In theory, these rules are substrate agnostic. Do they apply in other domains with repulsion behavior?

One example may be the optimal placement of, say, restaurants. If you have a McDonald’s on 30th St, it may not make sense to put another McDonald’s on 31st St. The existence of one McDonald’s exerts a repulsion pressure on all other McDonald’s. But wait! you might say. Surely there are countless examples of restaurants that serve the same food that are literally neighbors? That’s true. But intuitively, geographic distance on its own doesn’t capture everything. What really matters is foot traffic density. The repulsion pressure of one McDonald’s on another is inversely proportional to (distance * foot traffic). If you reweight distances by the inverse of their foot traffic, we might recover the optimal geometry again.

More abstractly, you could imagine that there is an optimal geometric spread of product categories. In the startup world there is a lot of hand wringing about whether something is a ‘feature’ or a ‘product’, whether a company has enough ‘differentiation’. The underlying principle is that products themselves exert repulsion pressure on other similar products. Even though we cannot exactly quantify how similar two products are, we can intuit that Dropbox and Google Drive are more akin than Dropbox and a Ferrari. If everyone is using Dropbox they may not use Google Drive. If everyone is using Dropbox, there’s basically no correlation to whether or not they will want to buy a Ferrari.

But here too we often have many similar brands competing with very similar product lines — what gives? Well, as with our restaurant example, we have to think about how the repulsion pressure is weighted. A product that is very cheap to make exerts less repulsion than one that is very expensive. And a product with a lot of demand also exerts less repulsion than one with no demand. So again, if you weight by the cost AND the demand, you might recover the original optimal geometries.

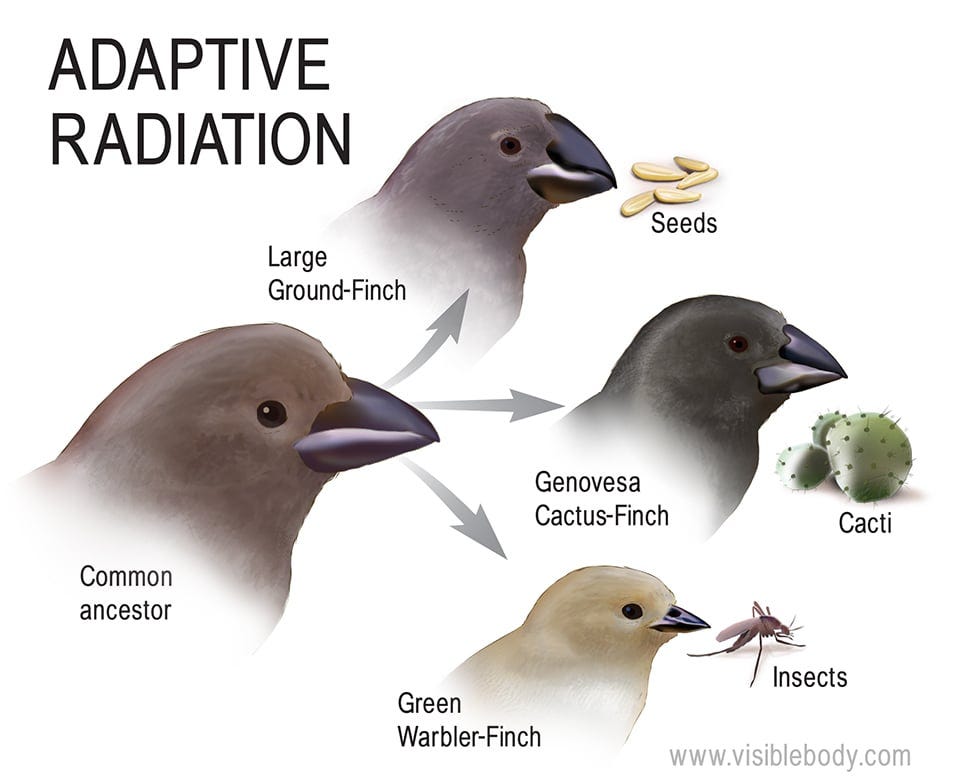

Speciation

Here’s something that’s interesting: you can basically always get better / “more optimal” results when you run multiple optimizers that are all optimizing for the same task in parallel, as long as those optimizers can’t easily reference each other.

An example of this in biology is speciation. Natural selection and reproductive isolation result in genetic diversity. That diversity results in stability and better outcomes over the entire cohort. Individual branches within the cohort may die out, but the overall collection does better (survives longer) the more diverse it is. Note that it is not enough to simply have a large population. For example, the Gros Michel banana was eaten all over the world, and at one point was the most common export banana. We’re talking millions of banana plants. But the plant itself wasn’t sufficiently genetically diverse, and the entire world population was essentially wiped out due to Panama disease. So the isolation-induced diversity is itself critical. Luckily we still have bananas in some form, because bananas as a larger cohort have more genetic diversity than just that one Gros Michel banana type.

We see the same behavior in economics. It’s taken as a truism that competition is necessary for innovation. When you have single monolithic companies that dominate a particular industry due to protectionism and government intervention, that industry stagnates. Competition mimics the natural selection / isolation pressures described above. Individual companies are ‘isolated’ in that they generally do not share information. And they are all optimizing for the same goal (market dominance, revenue, whatever particular objective function you want to use).

In ML, this phenomenon seems like it might map to boosting, mixture of experts (MoE) models, and to the self-play algorithms used by Deepmind to create AlphaGo/Star/Chess/Fold/Evolve. The latter are explicitly ‘genetic algorithms’, so named because they are directly inspired by the evolutionary pressures described above. But even the former two are about leveraging diverse exploration paths in loss landscapes to come up with better solutions than either individual path.

To abstract out a bit using familiar terms, you can model different species, different companies, and different models as methods of spending more ‘compute’ doing ‘parallel exploration’. In each case, there is some kind of tradeoff between compute and accuracy (where have we seen that before?). It again seems like there’s a general rule here that characterizes a certain class of optimization problem: any system with a single source of optimization pressure will encourage independent instantiations of optimizers against that optimization pressure source. Another way of thinking about this: assuming resources are not an issue, a cohort with more distinct optimizers (and some kind of pruning method) will arrive on a more optimal solution.

Can we see this rule apply in other domains? One example where this may apply is in the development of systems of governance. People in the United States sometimes speak of the ‘laboratory model’, where different cities / counties / states are all subject to optimization pressure from voters. These governing units will each independently try a bunch of different stuff, and the best policies are selected and moved forward while the losers get phased out. If you zoom out a bit, it seems like you could model all of civilization as a series of independent optimizers each trying to develop strategies for maximizing longevity.

Supply and Demand

I spent a lot of time at Google training GANs. A GAN is a generative adversarial network. They were created in 2014, and were the most common method of training models to do image generation until Stable Diffusion in 2022.

The basic idea is that you train two neural networks, a generator and a discriminator, with ‘opposing’ loss functions. The ‘generator’, attempts to generate images that can fool the discriminator, and the discriminator attempts to classify whether images are real or fake. GANs are notoriously fickle beasts. They have really strange equilibrium dynamics that make them unstable. In my experience, for any given GAN training run, there is a ~60% chance that the entire model would just fall apart.

The training dynamics of GANs always seemed somewhat similar to supply and demand behavior in classical economics. Supply and demand is a framework for understanding how two groups with different optimization criteria can discover an equilibrium point to execute a transaction. It also gives us a pretty clear language for explaining how suppliers and consumers can influence the pricing behavior of the other. Through supply and demand, we get to definitions of market efficiency and explorations of all of the ways markets can fail.

Maybe there are things that we can learn from economic interventions that we can apply to training GANs?

It turns out that the most common market failure mode is when one side of the market becomes way more powerful than the other. So we come up with all sorts of ways to weaken the more powerful side of the dynamic.

You could reduce asymmetric information advantages. For example, the government may mandate pricing transparency by requiring companies to publish how much it costs them to make their products. This seems similar to attempts to sideload additional data to the weaker GAN network.

You could introduce price controls, effectively preventing one side of the transaction dynamic from updating. This seems similar to learning schedules where either the generator or discriminator are held static for several steps while the other side is able to update freely.

You could change the optimization dynamics by introducing regulatory bodies or tax incentives. This seems similar to adding additional loss terms to different parts of the GAN.

To try and abstract out the pattern, it seems like optimization problems that involve two competing and opposite criteria have similar behaviors. They are often highly unstable due to the possibility of one side dominating the other. And there is a discrete set of interventions that you can take to make the system more stable. I’m obviously looking at all these things in retrospect. But maybe if we had a shared language for optimization, we would have been able to cross-apply what we know about economics to GANs without having to rediscover the same dynamics.

(In biology, homeostasis mechanisms feel very similar. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to see what the parallels are and whether there are interesting things that we can cross apply.)

Concluding thoughts

I would love to see more attempts at pulling out general rules like the scaling laws or like the laws of physics. Folks who think about optimization clearly have shared institutions that apply across domains. Yet it seems we have not done a great job documenting and trying to systematize those institutions. I totally admit that there are massive holes in my knowledge. Maybe there are many people out there who are doing this sort of work; if so, please link in the comments! Either way, I suspect that this is some of the most impactful kind of research we could be doing. Optimization has taken over our lives. It drives our media, it drives our politics, it drives our financial systems, it drives our cars. And soon it will drive intelligent automated systems. So we need to build a better language to describe these systems, so that we can create and manipulate them as easily as we do blocks of matter.

A mol has 6.022*10^23 atoms. Even if each atom could be described by a single bit, 10^23 bits is ~10 zettabytes of data

Note that a good friend of mine who studied econ and now does philosophy disagrees with this take! “From the Econ perspective: the field is actually extremely empirical and math-y (I was told as an undergrad that math majors would have a better chance of getting into top Econ phds than Econ majors), but perhaps not for the reason you’d expect. The field used to be very focused on developing law-like theories of the kind you seem to want up until the 70s ish. The problem is that almost all of them were wrong — or, less glibly, they were right about big trends but useless for making fine-grained predictions about specific policy changes. Things like the Laffer curve or the Phillips curve might contain useful insights (respectively that taxation past a high level can actually reduce revenue and that there’s a tradeoff between employment and inflation), but without any knowledge of where the actual numbers are, what the curve looks like, and where you are on the curve, you get an endless game of political football with no real guidance. Thus began the so-called “credibility revolution” in econ, where the field switched to being mostly about running linear regressions on large datasets to make very small and defensible claims about micro-level dynamics. This is also why I had no interest in being an econ PhD lol — I wanted to be able to make grand theories from the bathtub, but no economist gets to be Keynes or Schumpeter any more”

Great post, I found it really interesting. One area you didn't touch on here, that I've been thinking about myself, is fragility in the Talebian sense. If you consider the complex high-dimensional domains that we try to optimize, there are ones that we're good at, and ones that we're bad at.

Good:

> Biology / Medicine - antibiotics, blood pressure medicine, surgery etc all genuinely do wonders, when prior to antibiotics, any medical intervention was probably net negative from an All Cause Mortality perspective

> Global logistics - we routinely coordinate and solve incredibly complex allocation and timing problems at global scale

> Software - I'm personally amazed software works AT ALL, given that it's always this teetering tower of bullshit libraries calling a different suite of even worse libraries, with an ultimate dependency on one open source package some guy with health problems has been quietly maintaining for the last ten years (yes, that one xkcd), and it's all recursive and calls and interacts with both internal and external modules and functions with arbitrary complexity. And yet, it works!

> Space X - some guy took literal rocket science, the archetypical "difficult thing" that is a seething mass of complex dependencies and impossibly tight tolerances, and decided to make it more than 40x cheaper and more effective, and then *did it*

Bad:

> Economics and banking - both Taleb and Mandelbrot have proven that most of economics and banking is totally made up, "not even wrong," and cannot in principle ever predict the things they want to predict, and yet...they keep on doing it, I guess because they think you have to do *something* and these definitely-proven-wrong methods are something, so....

> Culture - as near as I can tell, there is not a single culture in the world that has top-down decided to go a certain direction, and then successfully gone there in a reasonable time and in a replicable way. Smoking is the closest thing we've got, and that took 60+ years, billions of dollars, and was STILL largely driven by the smokers literally dying off over that time period. This is kind of important, given current day issues like the fertility crisis in literally every developed country, and in the future various decisions about AI and AI-enabled things that could easily snipe large chunks of the populace (sexbots and Infinite-Jest style virtual heavens just off the top of my head, and that's without even considering any potential existential risks)

> Big projects - airports, metros, big software projects (Obamacare, etc), and more. Bent Flyvbjerg wrote the (excellent) book on this, but essentially with any given big project, it will nearly always run hundreds of percent over on both time and cost, and this is universal across countries and cultures. Heck, even small projects in the more ossified countries - in Tokyo or China, you can build a mid-rise building in a week, in the US, you'll spend a year and a third of the overall cost just on permits and bullshit before you can even break ground.

What distinguishes the good vs bad domains?

Why are we usually good at logistics, but then during Covid, we drop the ball and back up for years?

Why do we think we can do economics and banking, but they reliably blow up every decade or two?

Why have we polarized culturally, and can't get anything done any more?

Why do big projects always suck and massively overrun?

I'm not sure for most of these. But at least part of it is because a lot of our optimization techniques and regimes load us up on fragility - it's the old "picking up pennies in front of a steamroller" dynamic.

When we run a lot of optimization engines on local domains, we overfit on legible details, when there are illegible and / or unknowable details¹ that are many times more important than the legible details, and that can wreck everything. It's the black swans and fat tails. It's optimizing "slack" out of the systems, which counts as a local win but a significant increase in exposure to systemic risk.

And there is seemingly no paradigm that respects and ameliorates this tendency, and it's a greater risk in more domains the better we get at (locally) optimizing in a way that trades off for systemic risk, and that seems to be increasing everywhere.

I'm not sure what we need here - a "meta-optimization" framework? Different optimization regimes for different Talebian Mediocristan / Extremistan * payoff quadrants?

It seems important, and I basically never see anyone talking about it (besides Taleb's decade-old work), much less acting on it.

_______________________________________________________________________________

¹ As just one example, even if things *really are* Gaussian (which is usually NOT the case), the model error can make it impossible to predict things out at the tails:

“One of the most misunderstood aspects of a Gaussian is its fragility and vulnerability in the estimation of tail events. The odds of a 4 sigma move are twice that of a 4.15 sigma. The odds of a 20 sigma are a trillion times higher than those of a 21 sigma! It means that a small measurement error of the sigma will lead to a massive underestimation of the probability. We can be a trillion times wrong about some events.”

You may be interested in Cybernetics (the technical field, not the sci-fi term). Pioneered by Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics was/is an interdisciplinary synthesis of “Control and Communication in Animal and Machine.”

A lot of it builds on these sorts of common information/control structures. I’d recommend reading the original Cybernetics book by Wiener. Stanford Beer had some interesting stuff about “Management Cybernetics” which applied these ideas to companies or even countries. Dan Davies has a great substack that often touches on these subjects, and an excellent book, “The Unaccountability Machine.”

The field mostly died out or was absorbed into neighboring disciplines, for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to: the ease at which quackery can masquerade as complexity science, the US backed coup in Chile, Cold War tensions, and most notably, the fact that all of the really universal principles required vast amounts of domain specific knowledge to become even slightly useful, or couldn’t provide tight enough guarantees, or were intractable and needed to be replaced with particular heuristics. I pessimistically believe your “language of optimization” will either fall prey to this phenomenon, or is in fact a restatement of cybernetics itself.

But in another sense, Cybernetics lives on…

We live in a world where the synthesis of animal, machine, and digital is more complete than ever, a world Norbert Wiener predicted. Perhaps a new cybernetics is needed to make sense of the disparate complexities that ail us.